100th Anniversary Today

It isn’t often that we get hundredth anniversaries in media technology, so I figured this one — a double-header, actually — is worth mentioning. Today is the anniversary of the first live broadcast of a complete opera; yesterday was the 100th anniversary of the first live opera broadcast.

If that’s enough for you, stop reading, and go on to something else. But, if you’d like to learn a bit more about how opera made possible stereo sound, home entertainment, and even the newscast, read on. You have been warned, however, that this will not be a just a tiny nibble.

Radio pioneer Lee De Forest was an opera lover. The May 1907 prospectus of his Radio Telephone Company said, “It will soon be possible to distribute grand opera music from transmitters placed on the stage of the Metropolitan Opera House by a Radio Telephone station on the roof to almost any dwelling in Greater New York and vicinity.” He hired opera singers to sing into his microphones and also transmitted opera-music records, even from the Eiffel Tower.

Radio pioneer Lee De Forest was an opera lover. The May 1907 prospectus of his Radio Telephone Company said, “It will soon be possible to distribute grand opera music from transmitters placed on the stage of the Metropolitan Opera House by a Radio Telephone station on the roof to almost any dwelling in Greater New York and vicinity.” He hired opera singers to sing into his microphones and also transmitted opera-music records, even from the Eiffel Tower.

He reportedly couldn’t get Met general manager Giulio Gatti-Casazza to agree to allow a live radio broadcast, however, until De Forest pointed out that a stage microphone would also allow Gatti-Casazza to hear from his office what was happening on stage (though the previous general manager had already installed such a system). Finally, an experimental broadcast was authorized.

On January 12, 1910, Acts II & III of Tosca were sent by a transmitter at the Met, via an antenna strung between two masts on the roof, to a handful of receiving stations in the New York area. The New York Times accurately reported, “This will only be an experiment and perfect results are not expected immediately.” Those singing or talking into a microphone offstage were heard much better than those singing on the stage. Memory and imagination probably helped listeners.

Still, the world’s first live opera broadcast went fairly well. But, as is so often the case immediately after a reasonably successful experiment, the idea was exploited. Reporters were invited by the Dictograph Company, which provided the microphones, to hear two operas broadcast the next day, Cavalleria Rusticana and I Pagliacci, with superstars Emmy Destinn and Enrico Caruso.

The press invitation said the beautiful voices would be “trapped and magnified by the dictograph directly from the stage of the Metropolitan Opera House, and borne by wireless Hertzian waves over the turbulent waters of the sea to transcontinental and coastwise ships, and over the mountainous peaks and undulating valleys of the country.” In fact, on the 12th, there was shipboard reception, on a vessel docked at a Manhattan pier. As for the peaks and valleys, The Times had estimated a radius of perhaps 50 miles, given the low height of the opera-house roof.

On the 12th, others respectfully refrained from interfering with the broadcast. On the 13th, a report in Telephony said, “deliberate and studied interference from the operator of the Manhattan Beach station of the United Wireless Company” caused “some interruption.” “But,” according to The Times, “the reporters could hear only a ticking which the operator finally translated as follows, the person quoted being the interrupting operator: ‘I took a beer just now, and now I take my seat.'”

Oscar Hammerstein, whose Manhattan Opera House competed with the Met, installed a wireless station in his new London Opera House the next year. But it wasn’t for broadcasting; it was for selling tickets to “passengers in the great liners 500 miles out at sea,” according to The Times.

This is another opportunity for you to bail out and stop reading. Want to know a little bit more about early opera radio before the Metropolitan Opera’s Saturday-afternoon series began in 1931? Read on.

Before the First Live Opera Radio Broadcast

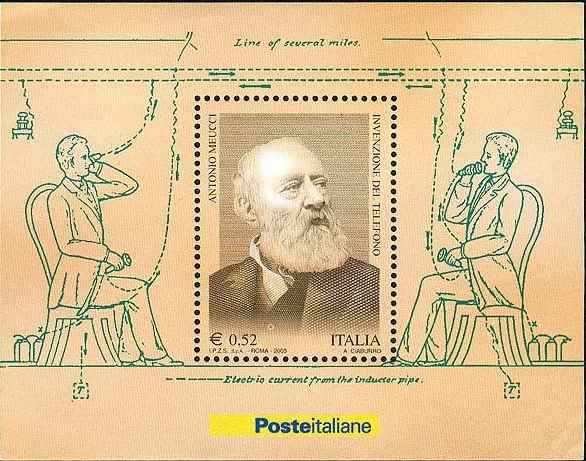

– In 1876 (55 years after opera broadcasts were predicted in The Repository of Arts), Alexander Graham Bell patented the telephone (whether Antonio Meucci, a former stagehand at Florence’s Teatro della Pergola opera house, actually beat Bell to the punch in 1849 experiments as technical director at Havana’s Teatro Tacón opera house is a different issue).

On March 22, The New York Times noted that “By means of this remarkable instrument, a man can have the Italian opera, the Federal Congress, and his favorite preacher laid on his own house.” In fact, they raised the box-office concern that “No man who can sit in his own study with his telephone by his side, and thus listen to the performance of an opera at the Academy, will care to go to Fourteenth street and to spend the evening in a hot and crowded building.” The following year, George du Maurier published a cartoon in which a household selected among opera offerings delivered by wire.

On March 22, The New York Times noted that “By means of this remarkable instrument, a man can have the Italian opera, the Federal Congress, and his favorite preacher laid on his own house.” In fact, they raised the box-office concern that “No man who can sit in his own study with his telephone by his side, and thus listen to the performance of an opera at the Academy, will care to go to Fourteenth street and to spend the evening in a hot and crowded building.” The following year, George du Maurier published a cartoon in which a household selected among opera offerings delivered by wire.

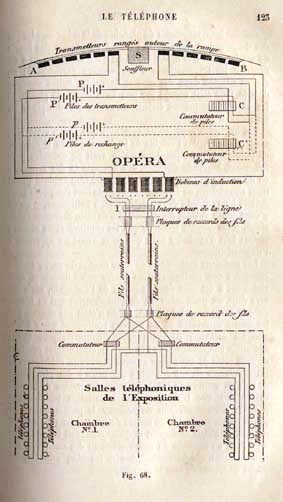

– In 1881, Clément Ader demonstrated the world’s first stereo transmission from the stage of the Paris Opéra. Multiple microphones fed multiple earpieces at the International Exhibition and Congress of Electricity. Listeners held a receiver to each ear to get immersed in the sound field. As the term stereo wasn’t yet in use for audio, the extensive report on the demonstration in Scientific American on December 31 of that year referred to it as binauricular auduition and said it provided an auditive perspective similar to what the stereoscope provided for vision.

– In 1881, Clément Ader demonstrated the world’s first stereo transmission from the stage of the Paris Opéra. Multiple microphones fed multiple earpieces at the International Exhibition and Congress of Electricity. Listeners held a receiver to each ear to get immersed in the sound field. As the term stereo wasn’t yet in use for audio, the extensive report on the demonstration in Scientific American on December 31 of that year referred to it as binauricular auduition and said it provided an auditive perspective similar to what the stereoscope provided for vision.

Possibly as a result of the 1881 experiment, an 1882 book science-fiction book by Albert Robida, Le Vingtième Siècle (The Twentieth Century), devoted an entire chapter to opera on TV. But, referring to Ader’s opera without visuals (before opera recordings or opera on the radio), a critic reported, “The telephone is a harsh judge.” Ader nevertheless pursued the idea of making delivery of live opera sound outside the opera house a permanent option.

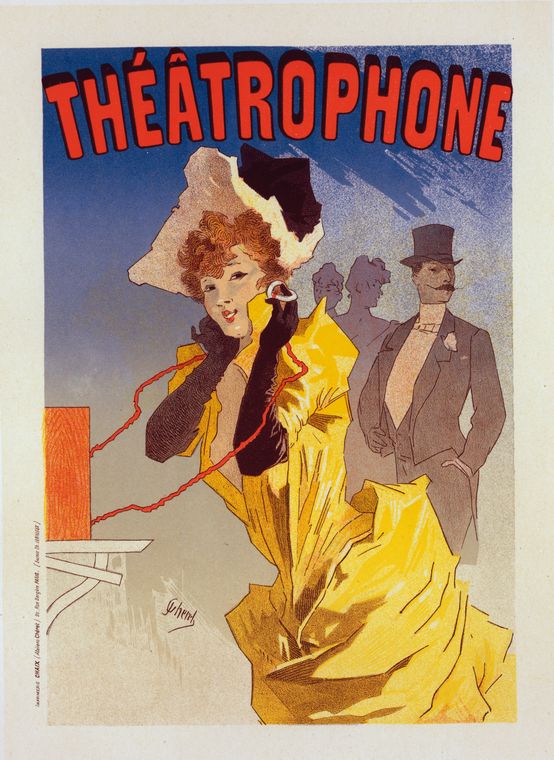

Commercial service followed, beginning in Portugal in 1885, delivering operas in stereo to homes and other locations, the world’s first electronic entertainment service for homes. The idea soon spread across much of the world, and, in 1891, the opening of the opera Le Mage in Paris was heard live in London. Marcel Proust was a Théâtrophone subscriber and wrote of listening to the opera Pelléas et Mélisande in bed at home.

– The Théâtrophone used a coin-operated business plan for its institutional service and a pay-per-event (plus subscription) plan for its home service. Ader’s Hungarian associate, Tivadar Puskás, chose a monthly-subscription model for his version, which began in 1893 (Nikola Tesla worked on the design). That meant that the lines were available when operas weren’t being transmitted, so the newscast was invented to give subscribers something to listen to before operas (and during intermissions). In 1930, the Hungarian service, Telefon Hírmondó (Telephone Herald), had 91,079 subscribers in Budapest alone who got the opera each night, with news reports during the intermission.

– In 1900, at the Paris Exhibition, Horace Short (like Ader, better known as an aircraft inventor) installed an “auxeto-gramophone,” a compressed-air-amplified record player, near the top of the Eiffel Tower and acoustically broadcast recordings of arias by stars of the Paris Opéra. The sounds could be heard throughout Paris, with no listening apparatus required.

– In 1904, Professor Otto Nussbaumer of the University of Graz in Austria sang into a microphone and was heard wirelessly next door, possibly the first vocal music carried by radio. The physics department head reportedly told him, “Your box works, but your singing is awful.”

Between the First Live Opera Broadcast and the Start of the Met Saturday-Afternoon Series

– In 1919, U.S. Navy transmitter NFF, at the time the world’s most powerful, broadcast live from the New Brunswick Opera House and was reportedly heard on a ship 2,000 miles at sea. In Chicago, the Signal Corps aired opera records.

Hugo Gernsback’s Proposal for Live Cinema Sound

– A 1919 proposal called for opera movies to be shot & distributed and projected to the singers, whose voices would be broadcast live to movie theaters to run in sync with the pictures. The Met’s first live cinema transmission (31 theaters in 27 cities) took place in 1952, with local TV stations having to agree to drop their network feeds so the coaxial cable could be used for the opera. Today, the Met’s Live in HD reaches more than 1,000 cinemas in 42 countries via satellite.

– In 1920, Nellie Melba sang into a powerful transmitter at the Marconi factory in Chelmsford, England and was heard throughout Europe and even across the Atlantic. In fact, the transmission was so powerful that it interfered with all others and was eventually shut down by the authorities. The Melba transmission was recorded in Paris, possibly the first off-air sound recording.

– The same year, four medical students in Buenos Aires had planned a single radio transmission, but, not wanting to be outdone by Marconi & Melba, changed it into an entire season of live operas broadcast from Teatro Coliseo in Buenos Aires. The first, on August 27, was Parsifal.

– On May 19 & 20,1921, the opera Martha was broadcast from Denver’s Municipal Auditorium by 9ZAF, a Special Amateur station said at the time to have had a range of 1500 miles. Reception was reported from Wyoming. This is believed to be the first opera broadcast by a station licensed to operate in the commercial radio band.

– In 1922, shortly before the Met broadcast a Veteran’s Day concert version of Aida from an armory, the real-life son of the singer playing Mimi stepped in as her lover Rodolfo after the tenor “got out of line” in an amateur Salt Lake City Bohème broadcast. An “elocutionist” described the action.

– In a 1924 Boston broadcast of Il Trovatore, the manager announced that the tenor couldn’t continue after the second act and a messenger would be sent to get Gaetano Tommasini as a replacement. Having heard the announcement in his hotel room, Tommasini arrived before the messenger left.

– AT&T’s WEAF (now WNBC) established a National Grand Opera Company in 1925, when it began weekly condensed-opera broadcasts. There was also a WEAF National Light Opera Company, both later taken over by NBC (which also ran a television opera company for 16 years).

– The 1927 inaugural broadcast of what is now CBS included a condensed version of Deems Taylor’s opera The King’s Henchman. A condensed version of African-American composer Harry Freeman’s opera Voodoo was broadcast in 1928 before being staged. And, in 1929, Cesare Sodero’s Ombre Russe became the first full opera to have its world premiere on radio (NBC) before opening in an opera house. But the first opera commissioned (by NBC) for radio (Charles Cadman’s The Willow Tree) didn’t premiere until 1932, and, in 1937, Louis Gruenberg’s Green Mansions was the first commissioned (by CBS) as a “non-visual opera.”

– In 1930, NBC carried a live broadcast of part of Fidelio from the Dresden State Opera House in Germany. The schedule noted it would be carried “atmospheric conditions permitting.”

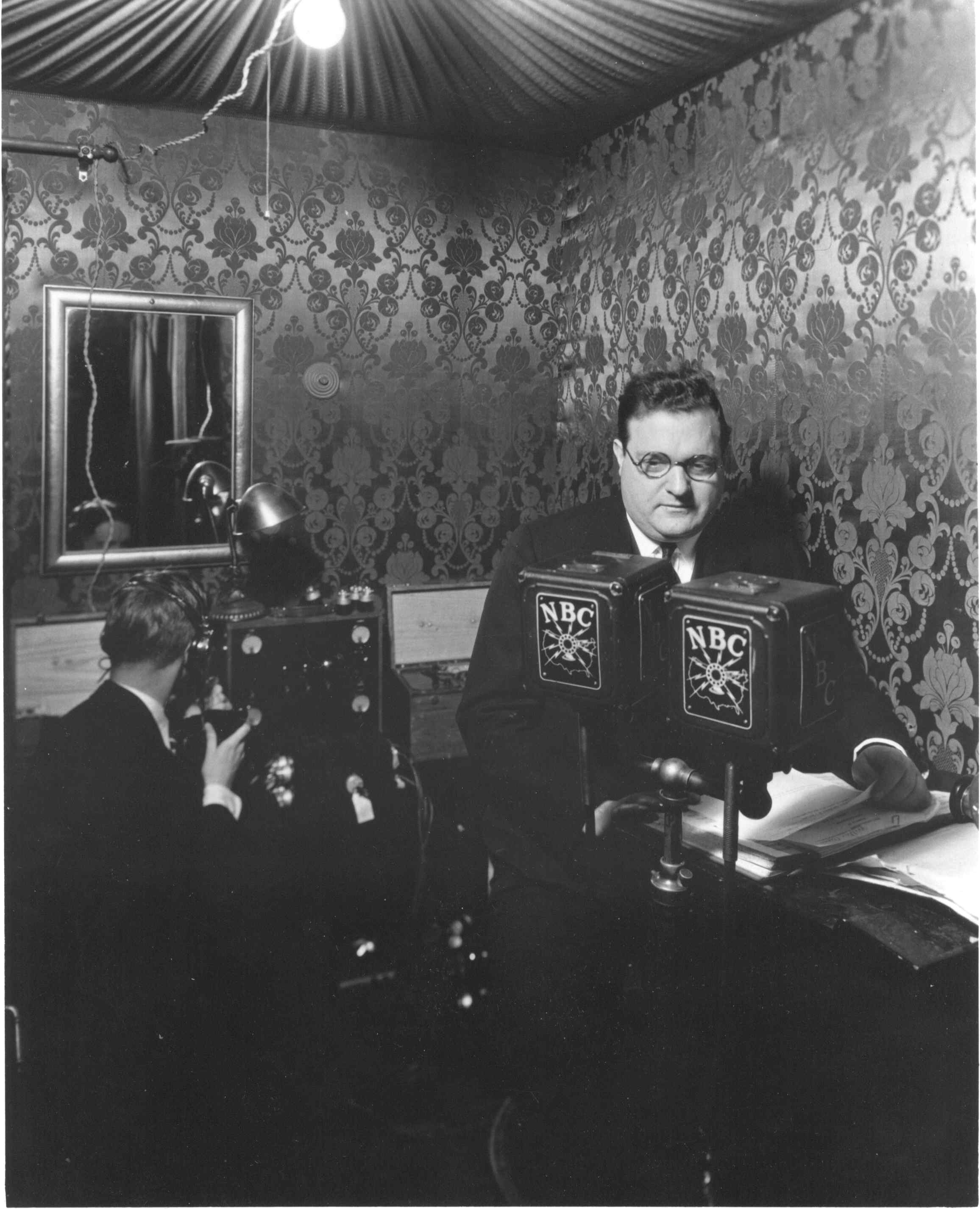

Milton Cross, one of only three permanent announcers in the history of Metropolitan Opera radio broadcasts

– In 1931, the Met began its live network opera broadcasts, which continue to this day (they were sponsored by the same company, best known as Texaco, from 1940 through 2004, said to be the longest continuous sponsorship in broadcast history). During the first broadcast, commentator Deems Taylor described the action during orchestral interludes, outraging opera purists, who called NBC, one woman saying she couldn’t hear what was going on because “some idiot keeps talking.” A telegram asked, “Is it possible to have Mr. Taylor punctuate his speech with brilliant flashes of silence?” But Taylor told the audience two weeks later, “We have received several thousand replies, of which fewer than 100 were opposed to being told what was going on upon the stage.” Nevertheless, the Met later restricted commentary to periods when the house lights were on.

And the rest — live TV, cinema, subtitles, satellite, Internet, HD, and even 3-D opera — is history.

Tags: AT&T, Caruso, CBS, Clement Ader, Deems Taylor, Emmy Destinn, Enrico Caruso, first opera broadcast, history, Lee de Forest, Milton Cross, NBC, Nellie Melba, Nikola Tesla, Opera, radio, telefon-hirmondo, theatrophone, Tivadar Puskas, Tosca, WEAF,

One comment

I think the Milton Cross audio “tent” decor is superb. I also like the pair of condenser microphones.

I grew up listening to the weekly broadcasts hosted by Milton Cross and recall vividly the first broadcast by Peter Allen in 1974 when I believe it was announced the day before Milton Cross had died.

Terry Harvey

The comments are closed.