The Motion-Picture Inventor (a baseball & opera story)

Story Highlights

In The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, originally a radio series broadcast in 1978, hyper-intelligent beings create a supercomputer to answer “the ultimate question of life, the universe, and everything.” After 7½ million years, the delivered result is 42. Author Douglas Adams denied there was any significance to the number. But it’s possible he was subconsciously influenced, and, for many, it’s possible that 42 was the answer.

Sports teams sometimes “retire” uniform numbers to honor players; the first was Ace Bailey’s 6, retired by hockey’s Toronto Maple Leafs in 1934. But 42 was retired across all teams in Major League Baseball, except for April 15, when all players wear the number. That’s the anniversary of the 1947 day when Jackie Robinson broke a racial barrier by playing for the Dodgers, wearing number 42.

It’s hard to conceive today of the impact he had at the time. It was a different age. Life, the universe, and everything changed.

Opera, too, had a racial barrier. When Marian Anderson performed as the fortune-teller Ulrica in Un ballo in maschera (“A Masked Ball”) on January 7, 1955, it was the first time an African-American sang a named role in a Metropolitan Opera production. Jackie Robinson served as master of ceremonies at a Fight for Freedom Fund event honoring the Met’s general manager, Rudolf Bing, for having invited Anderson to perform.

Opera, too, had a racial barrier. When Marian Anderson performed as the fortune-teller Ulrica in Un ballo in maschera (“A Masked Ball”) on January 7, 1955, it was the first time an African-American sang a named role in a Metropolitan Opera production. Jackie Robinson served as master of ceremonies at a Fight for Freedom Fund event honoring the Met’s general manager, Rudolf Bing, for having invited Anderson to perform.

Jackie Robinson was a hero. He changed the world. The retirement and mass wearing of 42 are well deserved. But he was not the first African-American to play major-league baseball.

Believe it or not, according to relatively recent discoveries by such baseball historians as Peter Morris and Bruce Allardice, the first was actually born a slave in Georgia in 1860. His name was William Edward White. In 1879, when the Providence Grays were in the National League, a player broke his finger. The team substituted White, a freshman playing for Brown University, in one game on June 21. He “played first base in fine style,” according to The Providence Journal.

White’s mother was light skinned, and his father was his mother’s owner. At least by the time he was at Brown, White’s name was also his designated race.

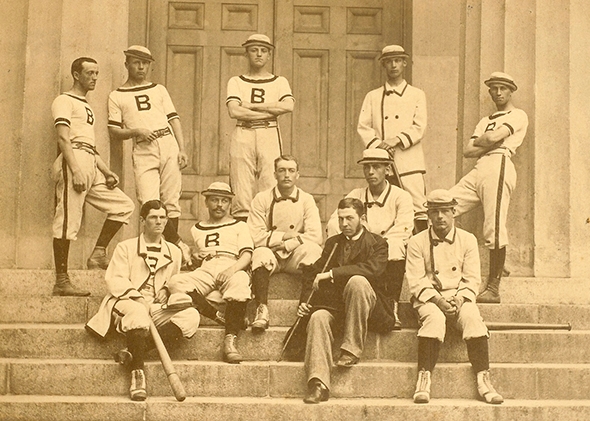

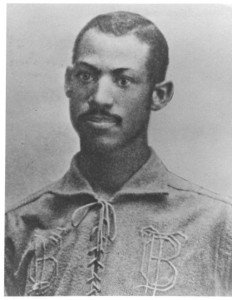

The first major-league baseball player known to have been African-American was probably Moses Fleetwood Walker, who, like White, played college baseball, first for Oberlin in 1877 and then, by invitation, based on his performance on the ball field, for the University of Michigan, where he studied law. He began playing semipro ball in 1881, but, when his team traveled to Louisville, locals kept him out of the game.

The first major-league baseball player known to have been African-American was probably Moses Fleetwood Walker, who, like White, played college baseball, first for Oberlin in 1877 and then, by invitation, based on his performance on the ball field, for the University of Michigan, where he studied law. He began playing semipro ball in 1881, but, when his team traveled to Louisville, locals kept him out of the game.

In 1883, he turned pro on the Toledo Blue Stockings of the Northwestern League. A league representative tried to ban “colored” players, but Walker’s performance killed the motion. The Toledo Blade said he “has been of greater value behind the bat than any [other] catcher in the league.” Sporting Life said, “Toledo’s colored catcher is looming up as a great man behind the bat.” But he still faced prejudice.

At an exhibition game, Cap Anson of the Chicago White Stockings didn’t want to play against a team with Walker on it. This time, his team backed Walker, and Anson relented when he learned he otherwise wouldn’t get paid. In 1884, the Blue Stockings joined the American Association, so Walker became a major-league baseball player — for a while. After an injury, he was released from the team.

There’s more to his baseball story (and even more to his life story, including his being acquitted by an all-white jury after killing a white man), but this is about baseball and opera. In 1885, Walker took over LeGrande House in Cleveland, among other things an opera house. It was the first of three he would run.

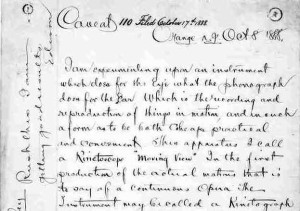

A case can be made that opera is the reason movies were invented. In the first caveat on the subject he filed with the U.S. Patent Office (in 1888), Thomas Edison listed opera as the only purpose of motion pictures. When Louis Le Prince had his French patent certified by the secretary of the Paris Opera in 1890, it was called “Method and Apparatus for the projection of Animated Pictures in view of the adaptation to Operatic Scenes.” Charles Francis Jenkins, the first president of the Society of Motion-Picture Engineers, referred often to opera; in his 1925 book Vision by Radio, he noted the importance of “a loudspeaker, so that an entire opera in both action and music may be received.”

A case can be made that opera is the reason movies were invented. In the first caveat on the subject he filed with the U.S. Patent Office (in 1888), Thomas Edison listed opera as the only purpose of motion pictures. When Louis Le Prince had his French patent certified by the secretary of the Paris Opera in 1890, it was called “Method and Apparatus for the projection of Animated Pictures in view of the adaptation to Operatic Scenes.” Charles Francis Jenkins, the first president of the Society of Motion-Picture Engineers, referred often to opera; in his 1925 book Vision by Radio, he noted the importance of “a loudspeaker, so that an entire opera in both action and music may be received.”

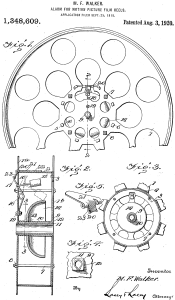

Walker did not invent movies, but, at his third opera house, in Cadiz, Ohio, he embraced the new medium. He found its technology wanting, however. Having previously (in 1891) received a patent for an artillery shell that would explode only at its target, Walker applied himself to such issues as alerting projectionists to film running out (diagram at right) and improved reels; he was awarded three patents in the field.

Walker did not invent movies, but, at his third opera house, in Cadiz, Ohio, he embraced the new medium. He found its technology wanting, however. Having previously (in 1891) received a patent for an artillery shell that would explode only at its target, Walker applied himself to such issues as alerting projectionists to film running out (diagram at right) and improved reels; he was awarded three patents in the field.

Moses Fleetwood Walker died in 1924. His number was not retired. In Toledo, however, he has been remembered in a modern-baseball way. On August 1, 2011, the Toledo Mud Hens gave each of the first thousand fans at their stadium a Walker bobblehead.