Everything Else

Story Highlights

Videotape is dying. Whether it will be higher in spatial resolution, frame rate, dynamic range, color gamut, and/or sound immersion; whether it will be delivered to cinema screens, TV sets, smartphones, or virtual-image eye wear; whether it arrives via terrestrial broadcast, satellite, cable, fiber, WiFi, 4G, or something else; the moving-image media of the future will be file based. But Hitachi announced at the International Broadcasting Convention in Amsterdam (IBC) in September that Gearhouse Broadcast was buying 50 of its new SDK-UHD4000 cameras.

Videotape is dying. Whether it will be higher in spatial resolution, frame rate, dynamic range, color gamut, and/or sound immersion; whether it will be delivered to cinema screens, TV sets, smartphones, or virtual-image eye wear; whether it arrives via terrestrial broadcast, satellite, cable, fiber, WiFi, 4G, or something else; the moving-image media of the future will be file based. But Hitachi announced at the International Broadcasting Convention in Amsterdam (IBC) in September that Gearhouse Broadcast was buying 50 of its new SDK-UHD4000 cameras.

Does the one statement have anything to do with the other? Perhaps it does. The moving-image media of the future will be file based except for everything else.

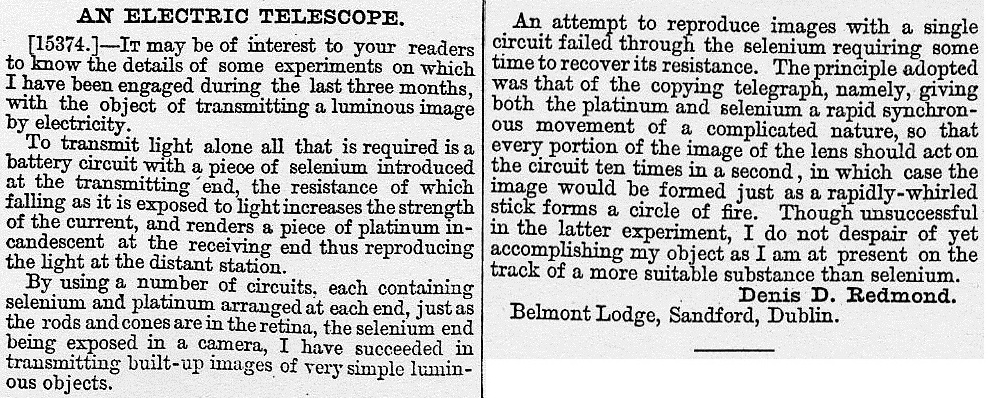

It might be best to start at the beginning. In 1879, the public became aware of two inventions. One, called the zoopraxiscope, created by Eadweard Muybridge, showed projected photographic motion pictures. The other, called an electric telescope, created by Denis Redmond, showed live motion pictures.

It might be best to start at the beginning. In 1879, the public became aware of two inventions. One, called the zoopraxiscope, created by Eadweard Muybridge, showed projected photographic motion pictures. The other, called an electric telescope, created by Denis Redmond, showed live motion pictures.

Neither was particularly good. Muybridge’s zoopraxiscope could show only a 12- or 13-frame sequence over and over. Redmond’s electric telescope could show only “built-up images of very simple luminous objects.” But, for more than three-quarters of a century, they established the basic criteria of their respective media categories: movies were recorded photographically; video was live.

Neither was particularly good. Muybridge’s zoopraxiscope could show only a 12- or 13-frame sequence over and over. Redmond’s electric telescope could show only “built-up images of very simple luminous objects.” But, for more than three-quarters of a century, they established the basic criteria of their respective media categories: movies were recorded photographically; video was live.

![]() It’s not that there weren’t crossover

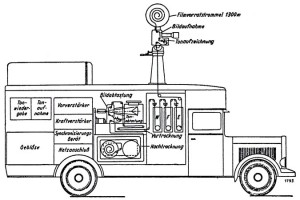

It’s not that there weren’t crossover  attempts. John Logie Baird came up with a mechanism for recording television signals in the 1920s. One of the camera systems for the live television coverage of the 1936 Olympic Games, built into a truck, used a movie camera, immediately developed its film, and shoved it into a video scanner, all in one continuous stream. But, in general, movies were photographic and video was live.

attempts. John Logie Baird came up with a mechanism for recording television signals in the 1920s. One of the camera systems for the live television coverage of the 1936 Olympic Games, built into a truck, used a movie camera, immediately developed its film, and shoved it into a video scanner, all in one continuous stream. But, in general, movies were photographic and video was live.

When Albert Abramson published “A Short History of Television Recording” in the Journal of the SMPTE in February 1955, the bulk of what he described was, in essence, movie cameras shooting video screens. He did describe systems that could magnetically record video signals directly, but none had yet become a product.

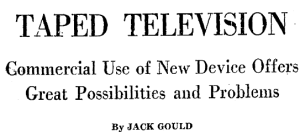

That changed the following year, when Ampex brought the first commercial videotape recorder to market. New York Times TV critic Jack Gould immediately thought of home video. “Why not pick up the new full-length motion picture at the corner drugstore and then run it through one’s home TV receiver?” But he also saw applications on the production side. “A director could shoot a scene, see what he’s got and then reshoot then and there.” “New scenes could be pieced in at the last moment.”

That changed the following year, when Ampex brought the first commercial videotape recorder to market. New York Times TV critic Jack Gould immediately thought of home video. “Why not pick up the new full-length motion picture at the corner drugstore and then run it through one’s home TV receiver?” But he also saw applications on the production side. “A director could shoot a scene, see what he’s got and then reshoot then and there.” “New scenes could be pieced in at the last moment.”

Even in his 1955 SMPTE paper, Abramson had a section devoted to “The Electronic Motion Picture,” describing the technology developed by High Definition Films Ltd. In 1965, in a race to beat a traditional, film-shot movie about actress Jean Harlow to theaters, a version was shot in eight days using a process called Electronovision. It won but didn’t necessarily set any precedents. Reviewing the movie in The New York Times on May 15, Howard Thompson wrote,”The Electronovision rush job on Miss Harlow’s life and career is also a dimly-lit business technically. Maybe it’s just as well. This much is for sure: Whatever the second ‘Harlow’ picture looks and sounds like, it can’t be much worse than the first.”

Even in his 1955 SMPTE paper, Abramson had a section devoted to “The Electronic Motion Picture,” describing the technology developed by High Definition Films Ltd. In 1965, in a race to beat a traditional, film-shot movie about actress Jean Harlow to theaters, a version was shot in eight days using a process called Electronovision. It won but didn’t necessarily set any precedents. Reviewing the movie in The New York Times on May 15, Howard Thompson wrote,”The Electronovision rush job on Miss Harlow’s life and career is also a dimly-lit business technically. Maybe it’s just as well. This much is for sure: Whatever the second ‘Harlow’ picture looks and sounds like, it can’t be much worse than the first.”

Today, of course, it’s commonplace to shoot both movies and TV shows electronically, recording the results in those files. A few movies are still shot on film, however, and a lot of television isn’t recorded in files, either; it’s live.

As this is being written, the most-watched TV show in the U.S. was the 2014 Super Bowl; next year, it will probably be the 2015 Super Bowl. In other countries, the most-watched shows are often their versions of live football.

As this is being written, the most-watched TV show in the U.S. was the 2014 Super Bowl; next year, it will probably be the 2015 Super Bowl. In other countries, the most-watched shows are often their versions of live football.

It’s not just sports — almost all sports — that are seen live. So are concerts and awards shows. And, of late, there is even quite a bit of live programming being seen in movie theaters — on all seven continents (including Antarctica) — ranging from ballet, opera, and theater to museum-exhibition openings. In the UK, alone, box-office revenues for so-called event cinema doubled from 2012 to 2013 and are already much higher in 2014.

It’s not just sports — almost all sports — that are seen live. So are concerts and awards shows. And, of late, there is even quite a bit of live programming being seen in movie theaters — on all seven continents (including Antarctica) — ranging from ballet, opera, and theater to museum-exhibition openings. In the UK, alone, box-office revenues for so-called event cinema doubled from 2012 to 2013 and are already much higher in 2014.

Files need to be closed before they can be moved, and live shows need to be transmitted live, so live shows are not file-based. They can be streamed, but, for the 2014 Super Bowl, the audience that viewed any portion via live stream was about one-half of one percent of the live broadcast-television audience (and the streaming audience watched for only a fraction of the time the broadcast viewers watched, too). NBC’s live broadcast of The Sound of Music last year didn’t achieve Super Bowl-like ratings, but it did so well that the network is following up with a live Peter Pan this year. New conferences this fall, such as LiveTV:LA, were devoted to nothing but live TV.

Files need to be closed before they can be moved, and live shows need to be transmitted live, so live shows are not file-based. They can be streamed, but, for the 2014 Super Bowl, the audience that viewed any portion via live stream was about one-half of one percent of the live broadcast-television audience (and the streaming audience watched for only a fraction of the time the broadcast viewers watched, too). NBC’s live broadcast of The Sound of Music last year didn’t achieve Super Bowl-like ratings, but it did so well that the network is following up with a live Peter Pan this year. New conferences this fall, such as LiveTV:LA, were devoted to nothing but live TV.

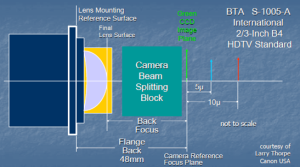

What about Hitachi’s camera? Broadcast HD cameras typically use 2/3-inch-format image sensors, three of them attached to a color-separation prism. The optics of the lens mount for those cameras, called B4, are very well defined in standard BTA S-1005-A. It even specifies the different depths at which the three color images are to land, with the blue five microns behind the green and the red ten microns behind.

What about Hitachi’s camera? Broadcast HD cameras typically use 2/3-inch-format image sensors, three of them attached to a color-separation prism. The optics of the lens mount for those cameras, called B4, are very well defined in standard BTA S-1005-A. It even specifies the different depths at which the three color images are to land, with the blue five microns behind the green and the red ten microns behind.

Most cameras said to be of “4K” resolution (twice the detail both horizontally and vertically of 1080-line HD) use a single image sensor, often of the Super 35 mm image format, with a patterned color filter atop the sensor. The typical lens mount is the PL format. That’s fine for single-camera shooting; there are many fine PL-mount lenses. But for sports, concerts, awards shows, and even ballet, opera, and theater, something else is required.

The intermediate-film-based live camera system at the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games was the size of a truck. Other, electronic video cameras were each called, in German, Fernsehkanone, literally television cannon. It’s not that they fired projectiles; it’s that they were the size and shape of cannons. The reason was the lenses required to get close-ups of the action from a distance far enough so as not to interfere with it. And what was true in the Olympic stadium in 1936 remains true in stadiums, arenas, and auditoriums today. Live, multi-camera shows, whether football or opera, are typically shot with long-range zoom lenses, perhaps 100:1.

The intermediate-film-based live camera system at the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games was the size of a truck. Other, electronic video cameras were each called, in German, Fernsehkanone, literally television cannon. It’s not that they fired projectiles; it’s that they were the size and shape of cannons. The reason was the lenses required to get close-ups of the action from a distance far enough so as not to interfere with it. And what was true in the Olympic stadium in 1936 remains true in stadiums, arenas, and auditoriums today. Live, multi-camera shows, whether football or opera, are typically shot with long-range zoom lenses, perhaps 100:1.

Unfortunately, the longest-range zoom lens for a PL mount is a 20:1, and it was just introduced by Canon this fall; previously, 12:1 was the limit. And that’s why Gearhouse Broadcast placed the large order for Hitachi SDK-UHD4000 cameras.

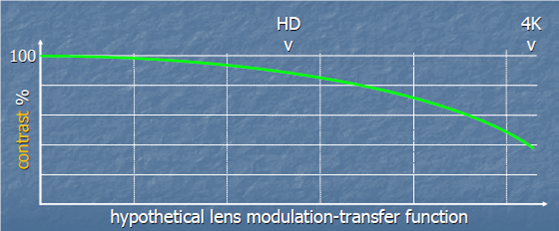

Those cameras use 2/3-inch-format image sensors and take B4-mount lenses, but they have a fourth image sensor, a second green one, offset by one-half pixel diagonally from the others, allowing 4K spatial detail to be extracted. Notice in the picture above, however, that although the camera is labeled “4K” the lens is merely “HD.” Below is a modulation-transfer-function (MTF) graph of a hypothetical HD lens. “Modulation,” in this case, means contrast, and the transfer function shows how much gets through the lens at different levels of detail.

Up to HD detail fineness, the lens MTF is quite good, transferring roughly 90% of the incoming contrast to the camera. But this hypothetical curve shows that at 4K detail fineness the lens transfers only about 40% of the contrast.

The first HD lenses had limited zoom ranges, too, so it’s certainly possible that affordable long-zoom-range lenses with high MTFs will arrive someday. In the meantime, PL-mount cameras recording files serve all of the motion-image industry — except for everything else.