White Space Databases Fail To Keep Wireless Microphones Safe

Without updated info, there’s no interference protection

Story Highlights

The White Space databases mandated by the FCC as part of the 600 MHz RF reallocation process have all but collapsed, according to some of the wireless-microphone manufacturers whose products and systems they were intended to protect.

Sennheiser’s Joe Ciaudelli: Professional mic operators currently lack an official resource that they can easily and confidently check for channel availability and register for interference protection.”

According to Sennheiser’s comments to the FCC last month in response to Microsoft’s appeal for more availability of white-space spectrum putatively to expand broadband into more rural areas, “All TV white-space portals of FCC-approved administrators were offline” for certain periods in the last two years. “There was no way to register for interference protection from [white-space devices] or for wireless microphone operators to check for local channel availability. Nor can the FCC TV Query database fill that role. Prior to commencement of the 600 MHz transition, this database was updated daily by the commission. Today, however, it is woefully out-of-date because none of the repacked TV stations are reflected.”

Microsoft asserts that White Space spectrum is critical to closing the rural digital divide (aka Microsoft’s Airband initiative) between urban areas well served by broadband availability and rural areas nearly devoid of it. Joe Ciaudelli, director, spectrum affairs, Sennheiser, a manufacturer of wireless mics, says that’s a laudable goal but the software giant is also stretching the FCC’s definition of “less congested” airwave areas, asking the agency to relax the rules around White Space deployment and to extend the legal use of white-space devices (WSDs) into denser RF territory, where it could interfere with registered professional wireless-microphone users.

Databases Gone Dark

This territorial issue is exacerbated by the lack of formal registration databases that wireless users could check for channel availability in areas they need to work in and through which professional users could reserve channels for specific periods of time. The White Space databases were established in 2012 by the FCC to manage the spectrum available to WSDs while protecting licensed (and, in some cases, unlicensed) users. Initially, four White Space database administrators were authorized by the FCC to accept wireless-microphone registrations: Google, Key Bridge Global, LStelecom/RadioSoft, and Spectrum Bridge.

Ciaudelli explains that, early in the RF-reallocation process, WSDs looked to become a huge new consumer-electronics category, offering the potential for significant revenue for the administrating companies. However, the market never developed as expected, with just a handful of commercial users, so far using it for such applications as distributing announcements in venues.

Shure’s Mark Brunner says the underdeveloped WSD consumer market aids spectrum management somewhat but leaves a long-term problem.

“A stadium might be using white-space devices to broadcast to fans where to park when they arrive and which exits to use when they leave,” he says. “There were more white-space devices in PowerPoint presentations than in people’s hands.”

Once it became clear that there was no gold in that pan, the administrators left after the expiration of their five-year commitment terms. That occurred from 2017 in 2018, halfway through the FCC’s three-year period of repacking the broadcast spectrum following the latest auction.

Last September, Nominet, a UK domain-name–management company that also manages the TVWS rural-broadband database for the country’s Ofcom media-technology ministry, gained FCC approval as a TV White Space database administrator in the U.S. However, Ciaudelli points out that, thus far, Nominent’s website has provided limited functionality for wireless-microphone operators.

“The problem,” he asserts, “is that the system of database administrators collapsed. Professional mic operators currently lack an official resource that they can easily and confidently check for channel availability and register for interference protection.”

Failure To Function

Ironically, the underdeveloped WSD consumer market actually helps spectrum management slightly at the moment, by making it less dense and leaving some spectral breathing room for professional wireless users. But, says Mark Brunner, VP, global, corporate, and government relations, Shure, that leaves a long-term problem in place.

“That [WSD] ecosystem could still develop in the future,” he says, “and the control mechanisms for it needs to be in place and functioning.”

Shure, Sennheiser, and other wireless-systems manufacturers have filed notices with the FCC about the databases and about Microsoft’s proposed changes to the 2014 rules for allowing unlicensed use of the white spaces. A key argument asks, how can any changes to rules take place without the spectrum management mandated by the RF-reallocation process in place and functional?

“The NAB has raised the flag about this, so the FCC has been made aware,” says Brunner. “But what action they take remains to be seen.”

He says he has spoken with key wireless-microphone users on the topic, noting their frustration as they try to follow the rules without the critical guidance of the database information.

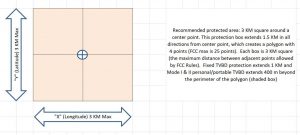

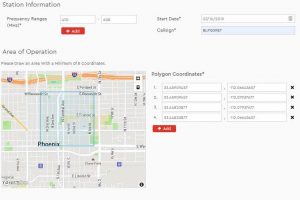

Sample polygon protection using Nominet’s 600 MHz cellular registration filed by Karl Voss. Note the error because he tried to specify frequencies outside 600 MHz.

Interesting Season Ahead

Karl Voss, lead frequency coordinator, NFL, says he has been compelled to navigate the thicket of bureaucracy behind the scenes in an attempt to register licensed wireless mics through Nominet. He met with the UK-based company during the NFL game played in London earlier this year. Part of the problem, he explains, is Nominet’s inability to provide polygon protection, a type of RF protection for large venues, such as golf courses and football stadiums. Instead, he must apply for multiple point/radius protections on a venue-by-venue basis. A polygon type of protection allows each venue to be specified by its four corners (as per FCC rules); although the FCC limits the number of points in a polygon request to 25, some of the now-obsolete White Space databases limit the number of points to 16, allowing only up to four NFL venues to be protected in a single request. That means the process must be repeated eight times to cover the league’s 32 stadiums.

Voss further points out that Nominet’s portal can provide polygon protection for wireless devices in the 617-698 MHz range but adds that any professional wireless-microphone system using those frequencies is essentially (though not intentionally) cloaking itself as a cellular provider, which is not what the FCC intended.

But he is unhappy that he has to go to these lengths, given that the FCC had putatively provided a management mechanism for RF management as part of the complex RF-reallocation process and that that mechanism has broken down: “It could make for a very complicated season for RF this year.”