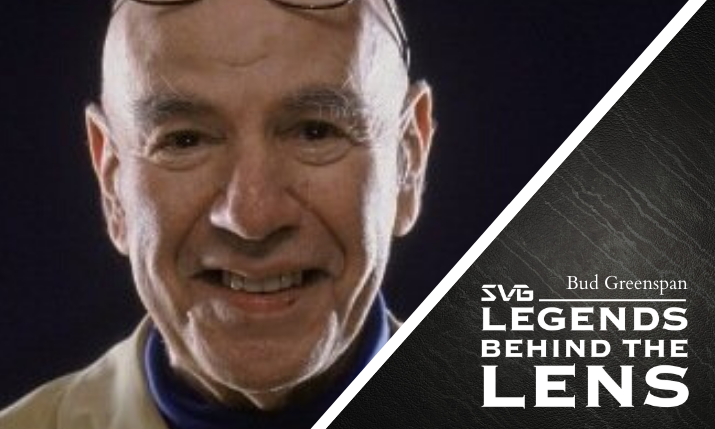

Legends Behind the Lens: Bud Greenspan

The legendary documentarian brought out the humanity in seemingly impossible Olympic achievement

Story Highlights

The story of American sports television is engrained in the history of this nation, rising on the achievements of countless incredible men and women who never once appeared on our screens. During this pause in live sports, SVG is proud to present a celebration of this great industry. Legends Behind the Lens is a look at how we got here seen through the people who willed it to be. Each weekday, we will share with you the story of a person whose impact on the sports-television industry is indelible.

Legends Behind the Lens is presented in association with the Sports Broadcasting Hall of Fame and the SVG Sports Broadcasting Fund. In these trying times — with so many video-production professionals out of work — we hope that you will consider (if you are able) donating to the Sports Broadcasting Fund. Do so by visiting sportsbroadcastfund.org.

___________________________

By PJ Bednarski

Late TV-journalism pioneer Don Hewitt titled his autobiography Tell Me a Story. That would also be an apt title for a book about the late Bud Greenspan, whose legendary Olympic documentaries were less about the heroes than they were about the often heartbreaking, often exhilarating stories of athletes in competition and away from it.

“We don’t do sports as much as we do people,’ Greenspan used to say. And he didn’t do sadness or defeat as much as he did victory: victory of spirit, if not always the kind of victory that earns medals.

“There are people who do negative better than I,” he told the New York Times. “I want to spend my time on what’s good.”

The proof of that was in the documentary Lillehammer ’94: 16 Days of Glory, his chronicle of the 1994 Winter Olympic Games. Those Games will forever be remembered for the Nancy Kerrigan-Tonya Harding figure-skating fracas that shocked, riveted, and repulsed the world. But, in Greenspan’s 209-minute film, that grimy crime got 30 seconds.

“I was offended,” he said later. “These are asterisks in my films and in my stories. For our business to make such a big deal out of people who are illegal and immoral is not what I intend my life to be.”

Greenspan ran the company from his early days with his much beloved wife, Cappy, who died of cancer in 1983. After her death, he ran the company he named after his wife with his business partner and companion Nancy Beffa. She was executive producer of Lillehammer and still runs Cappy Productions.

Greenspan documentaries also captured Olympic Games in Seoul (1988), Barcelona (1992), Atlanta (1996), Nagano (1998), Sydney (2000), Salt Lake (2002), Athens (2004), Torino (2006), Beijing (2008), and, released after his death, the 2010 Winter Games in Vancouver. He also produced many other Olympic-themed works, such as Jesse Owens Returns To Berlin, his 1964 documentary about the visit by the African-American runner whose four gold medals at the 1936 Berlin Games mocked Adolph Hitler’s claims of Aryan superiority.

He also directed 100 Years of Olympics Glory. Greenspan, who was born in 1926 and died in 2010 from Parkinson’s disease, used to joke that he really hadn’t been to all of them; it just seemed like it.

Beffa recalls, “Bud always said, ‘Every Olympic athlete needs four things: pride, talent, courage, and the ability to endure.’“

“Bud is a great filmmaker. I think he really pulls out of a story the true essence of who he’s trying to depict. He captures the mystery, the magic, and the wonder of having never done it before.” – Olympic swimmer Mark Spitz

That philosophy didn’t necessarily set him aside from others who covered the Games. But some circumstances did. For one, Beffa says, Greenspan didn’t care where the athletes were from. For another, he didn’t particularly care if the sport they played was well-known. And he didn’t care if they didn’t win.

The best example of all of that — indeed, one of the indelible examples of Greenspan’s style — happened at the 1968 Summer Games in Mexico City.

John Stephen Akhwari, representing Tanzania in the Marathon event, was seriously injured during the run. But he kept on, in obvious pain, limping on a bandaged right knee and finishing the race more than an hour after everyone else.

Later, Greenspan asked Akhwari why he didn’t quit. “I don’t think you understand,” the runner told him. “My country didn’t send me 9,000 miles to start the race. They sent me 9,000 miles to finish the race.”

That footage, painful and powerful, could make a stone cry.

Greenspan, forever with a pair of glasses on top of his bald head, came to sports documentaries in an odd way.

After serving in World War II as an intelligence officer, he returned to his native New York and quickly forged a career in radio at the old WHN, becoming its sports director in his early 20s.

But he also loved opera and thought he could sing. To make extra money, he got work in 1952 as a spear carrier in the chorus. He didn’t have a voice after all. (“Greenspan,” the choirmaster said to him one day, “I don’t even want you to ‘mouth.’“)

While in the chorus, he met John Davis, an African-American baritone, who was, despite having won Olympic gold medals in 1948 and ’52 as a heavyweight weightlifter, was unknown to most sports fans. Greenspan was astonished. And that led to his first documentary, The Strongest Man in the World, made with a borrowed $5,000.

He couldn’t sell it, though. He was in a panic, he recalled later when he received his Peabody Award for lifetime achievement.

Luckily, he learned that the State Department was looking for something to show at consulates to counteract Soviet propaganda about U.S. treatment of black athletes. But, they said, they could offer “only” $50,000.

“I said, ‘This is a good business,’” he told the awards luncheon crowd. And a business was born.

Financing Greenspan’s documentaries took a lot of angel investors and shrewd negotiations. And the big networks worldwide tried to claim the best camera berths and other perks from Olympics organizers.

“As an indie,” Beffa says, “when it came to negotiating for camera locations, we were always at the bottom of the food chain. Half the time, we didn’t know what we were going to do.”

But, she says, Greenspan had made friends around the world by covering athletes from different countries. They tipped him to interesting stories; in fact, that’s how he heard about the marathon runner. When negotiating with host countries, Greenspan reminded them that his film mission was to celebrate, not denigrate. That helped.

Greenspan was among the first to popularize documentary styles like showing crowd reactions to tell the story. “When we lectured filmmakers in other countries,” Beffa recalls, “Bud would always tell them, ‘Let your shot go long.’” It was a technique that he used in more than a few stunning scenes instead of quickly cutting away.

He died before the ease of creating videos via smartphones reached just about every corner of the world.

How would he react to that? Beffa says, “I think he would see these short pieces and say they are well-edited. It would be nice. But they would be forgettable. They wouldn’t tell a story.”