SVG Tech Insight: Cloud-Based Live Production – What Can We Expect?

Story Highlights

This spring, SVG will be presenting a series of White Papers covering the latest advancements and trends in sports-production technology. The full series of SVG’s Tech Insight White Papers can be found in the SVG Spring SportsTech Journal HERE.

Cloud-based technologies are gradually finding their way into our workflows. Will this influence how we produce? The answer is most likely “yes”. What is even more interesting, though, are the “when” and “how”.

A global pandemic that questions everything we used to take for granted may not be the perfect time to look ahead and wonder what live production scenarios will be in the future, or how manufacturers may contribute to this vision. Yet, history shows that exceptional circumstances often inspire innovation.

Distributed, networked production setups that kickstart collaborative production scenarios have proven tremendously useful for broadcasters and service providers to make it through the pandemic despite substantial restrictions regarding content creation. What once looked daring to some served a specific need from day one and laid the foundation for what is either available or announced today: remote production over a wide-area network, with a clear aim to work more efficiently and control cost. This direction has whetted operators’ and C-suite officers’ appetite for more.

This white paper explores how the difference between local and remote, between WAN and LAN, between small and large can be made irrelevant in a way that satisfies all stakeholders.

The Fuzzy Cloud

For most of us, the “cloud” is already everywhere: in our daily office work, homeschooling, meetings, and international collaboration projects. Who would have thought it would be so pervasive only a year ago? Working “in the cloud” has literally been a lifesaver, even though we also realized that some cloud-based services work better than others. Based on our mostly positive experiences, however, we are no longer wary of what the cloud may bring.

Some services we use for production are already being virtualized and abstracted from their physical backbone, which is hosted on-premise, in a hub, or in the cloud ‘somewhere’. Soon, monitor walls will be populated with PiPs via intuitive UIs, grabbing sources that are available on the network but whose points of origin may be unknown.

See You in the Cloud!

Players in the broadcast sector are ready to embrace this new vision; manufacturers are asked to rehost their products on COTS platforms or proprietary but software-defined hardware solutions rather than on dedicated devices. Some of the required solutions will need to be rebuilt for virtualization, as not all existing platforms can be ported to an all-new environment as is.

When this migration is complete, and every device has been turned into a “cloud-enabled” service, the underlying processes can be outsourced to tech centers, at first on an organization’s own campus, but ultimately operated by third-party specialists, in places where real estate is more affordable. Somebody will look after those machines, maintain optimized environmental conditions, and provide transparent commercial plans. Broadcasters will be able to select which, and how many, of these services they need at any given point in time to deliver value-added productions. Additional resources will be available on demand, and releasing resources you no longer need will be easy. Pay-as-you-go at its very finest…

This still sounds a bit like science fiction, right? It certainly is a bold prospect for high-profile live productions. Look closer, though, and you will realize that “the cloud” can have many shapes and guises — in any combination.

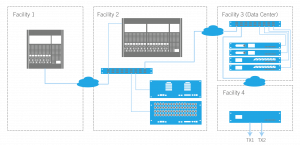

Figure 1: A cloud-based production scenario with signal generation, processing, playout, and control surfaces completely separated

Cloud-Connected

In a virtualized environment, operators no longer know where the processing takes place — and most of them do not really care, as long as the result meets all quality, latency, and timing requirements.

This is an important aspect for virtualized production scenarios: most operators have little difficulty accepting geo-agnostic setups, provided they work as reliably as the dedicated machines of yore. The overall production system can therefore be scattered over several locations for more flexibility.

As a result, operators, control surfaces, and user interfaces can be moved around, because the distance to the processing services becomes irrelevant. This does not mean, however, that any task can be performed just about anywhere. Audio mixing, for one, requires a sound-proofed environment, while a vision mixer needs to be close to the monitor wall and the producer. And cameras and microphones still need to be pointed at the players or athletes.

As most of us will confirm, separating edge devices from the processing units and control activities over a wide-area network makes a lot of sense, both financially and from an agility perspective. This is not new, by the way: lots of operators have been applying this principle for a while. No wonder cloud and/or edge connections to the backend are on the rise: it was always going to be this way.

Bend Me, Shape Me…

What sounds promising on paper, though, is still a little more complex than we like to believe. FPGA-based signal converters can be tasked with conversion operations (from 1080i to 1080p, say), and their built-in web interface allows users to set a host of additional parameters. Such solutions are able to transmit their settings and status information to an interface, which communicates with an overarching control system.

The latter then takes care of ensuring that the video and audio data received by the signal converter as RTP streams are processed and injected back into the network, while also acting as the main control interface for all tasks going on simultaneously.

Assuming that a PaaS/IaaS provider offers adequate hosting solutions and sufficient bandwidth for transporting the required data between the operator and the process, nothing should stand in the way of moving the entire production process into the cloud.

Look closer, though, and it becomes clear that migrating all signal processing tasks to external systems may be just a little too ambitious for now — for all sorts of technical reasons. So why not look at the “cloud” from a different angle?

The drive to move everything “into the cloud” is essentially based on our desire to use the required resources more flexibly and the processes that provide them as effectively as possible. This can already be achieved by managing such resources — audio cores, video processors, etc. — from a central location and by treating them as “pools”, or private clouds, whose processing magic is available on demand, 24/7, from any location, over a secure WAN or campus link. Immediately, broadcasters would be able to produce more efficiently. A larger audio control room located elsewhere could be utilized for a short-notice production in studio XYZ, even if they weren’t initially scheduled for collaboration.

Examples of “permanent remote setups” that were architected with exactly these considerations in mind abound. Using software-defined hardware not only makes such devices more versatile but also offers the advantage that you can contact a highly competent partner who understands what the issue is and how to remedy it. However, none of the scenarios necessarily require a cloud service provider.

Whatever your preferred scenario, there will be a transitional phase during which broadcasters will work with a public/private cloud (and perhaps even onsite) hybrid, because of the unavailability of specialist processes on one platform. What really matters today — and in the foreseeable future — is the ability to access the required resources as and when they are needed.

Idle resources need to be logged by a central orchestrator and accessible to operators who require them. User-specific data — audio, video, and control — need to find their way to these resources automatically, without any user interaction.

Breaking complex processes down into micro services promises to add even more flexibility regarding their location and availability. This still requires “someone” who knows that they exist and establishes a route between them and the operator (or routine) who requires them. Ideally, such a management system should treat public and private clouds as well as on-campus solutions as equals and present the processes they host to operators based on specific requirements, with as little manual configuration as possible.

Think of it as the sequel to a control and orchestration system that welcomed IP-based solutions amid a pool of baseband devices and made the disparity manageable for production purposes. Only more powerful and offering a breath-taking immediacy on a much wider scale. And way more intuitive.

Welcome Home

Let us agree, for now, that “the cloud” for broadcast applications is a collection of services that coexist in a variety of spaces and can be securely and reliably accessed from any location. It may consist of proprietary devices until they reach EOL, centralized processing hubs (which are, in essence, private clouds) whose resources are shared as well as software and micro services running somewhere.

Its most relevant aspect is that these services are registered as soon as they come online and allocated to operators, irrespective of where they are based and when they need them. This can be achieved with a solution that clears the fog, automates all pesky configuration tasks and ensures unrestricted access to whatever may be needed to produce pristine content in any format today’s audiences expect. Wouldn’t that be the silver lining we have been working towards?