The Bottom Line

Like many other innovations, high-dynamic-range (HDR) imaging can bring benefits but will require work to implement. And then there’s the bottom line.

HDR’s biggest benefit is that it offers the greatest perceptual image improvement per bit. Different researchers have independently verified the improvement, and it theoretically requires no increase in bit rate whatsoever. In practice, to allow both standard-dynamic-range (SDR) TVs and HDR TVs to be accommodated with the same signal (and because not everyone keeps the appropriate amount of noise), the bit rate might increase a small amount — perhaps 20%.

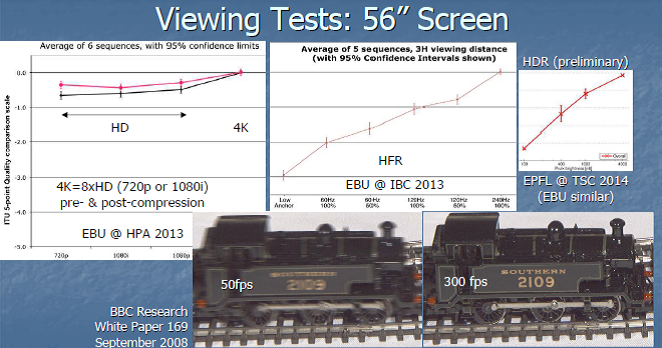

Above are comparisons of viewer evaluations of higher spatial resolution (e.g., going from HD to 4K) at left, higher frame rate (HFR) in the middle, and HDR at right, with the vertical scales normalized. The distance from the top shows the improvement. To achieve the improvement that HDR delivers with a zero-to-20% increase in bit rate, HFR would need a 100% increase or more. Going to 4K from HD can’t even approach the HDR improvement, but, if it could, it would seem to require more than a 1600% increase in bit rate. HDR is the clear winner.

That’s one piece of HDR good news. Another is that it can deliver more colors separately from any increase in color gamut. It also allows more flexibility in shooting and post production. And it doesn’t appear to require any new technologies at any point from scene to seen.

Below is an image presented at the 2008 SMPTE/NAB Digital Cinema Summit. It was shot in a Grass Valley lab using the Xensium image sensor. The only light on the scene came from the lamp aimed at the camera at lower right, but every chip on the chart is distinguishable. From lamp filament to darkest black, there was a 10,000,000:1 contrast ratio, more than 23 stops of dynamic range. And, on the viewing end, TV sets have already been sold with HDR-level light outputs. New equipment might be needed, of course, but not new technologies.

That’s the good news. Getting everyone to agree on how HDR images should be converted to video signals, how those signals should be encoded for transmission, and how SDR and HDR TV sets should deal with a single transmission path are among the issues being worked out. They’ll be discussed at next month’s HPA Tech Retreat. And then there are interactions.

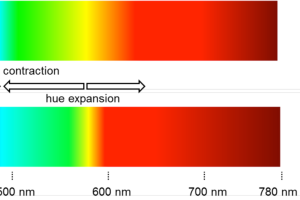

Sean McCarthy of Arris offered an excellent presentation on the subject at the main SMPTE conference last fall. Appropriately, it was called “How Independent Are HDR, WCG [wide color gamut], and HFR in Human Visual Perception and the Creative Process?” Those viewing HDR-vs.-SDR demos have sometimes commented that image-motion artifacts seem worse in HDR, suggesting that HDR might require HFR or restrictions on scene motion; McCarthy’s paper explains the science involved. It also explains how color hues can shift in unusual ways, becoming yellower above certain wavelengths and bluer below as light level increases, as shown in an excerpt from an illustration in McCarthy’s paper above at right (higher light level is at top).

Sean McCarthy of Arris offered an excellent presentation on the subject at the main SMPTE conference last fall. Appropriately, it was called “How Independent Are HDR, WCG [wide color gamut], and HFR in Human Visual Perception and the Creative Process?” Those viewing HDR-vs.-SDR demos have sometimes commented that image-motion artifacts seem worse in HDR, suggesting that HDR might require HFR or restrictions on scene motion; McCarthy’s paper explains the science involved. It also explains how color hues can shift in unusual ways, becoming yellower above certain wavelengths and bluer below as light level increases, as shown in an excerpt from an illustration in McCarthy’s paper above at right (higher light level is at top).

Then there’s time. McCarthy’s paper explains how perceived brightness can change over time as human vision adapts to higher light levels. And there’s also an inability to see dark portions of an image after adaptation to bright scenes. “In bright home and mobile viewing environments,” McCarthy notes, “both light and dark adaptation to [changes] in illumination may be expected to proceed on a time scale measured in seconds. In dark home and theater environments, rapid changes going back and forth from [darker to lighter light levels] might result in slower dark adaptation.” In other words, after a commercial showing a bright seashore or ski slope, viewers will need some recovery time before they can perceive dim shadow detail.

HDR also brings concerns about electric power. It’s often said that the high end of the HDR range will be used only for “speculars,” short for specular reflections, like glints of lights on shiny objects, as shown on these billiard balls, from Dave Pape’s computer-graphics lighting course. If so, an HDR TV set would be unlikely to need significantly more electric power than an SDR TV set.

HDR also brings concerns about electric power. It’s often said that the high end of the HDR range will be used only for “speculars,” short for specular reflections, like glints of lights on shiny objects, as shown on these billiard balls, from Dave Pape’s computer-graphics lighting course. If so, an HDR TV set would be unlikely to need significantly more electric power than an SDR TV set.

Those snow and seashore scenes, however, could need a lot more power if shown at peak light output. At right is a scene shown in promotional material for a Samsung HDR-capable TV, with bright snow, ice, and clouds. Below is a section of the technical specifications of the Samsung SUHD JS8500 series 65-inch TV. As shown below, the “typical power consumption” is 82 watts, but the “maximum power consumption” is 255 watts, more than three times higher. The monitor used in Dolby’s HDR demos is liquid cooled.

Those snow and seashore scenes, however, could need a lot more power if shown at peak light output. At right is a scene shown in promotional material for a Samsung HDR-capable TV, with bright snow, ice, and clouds. Below is a section of the technical specifications of the Samsung SUHD JS8500 series 65-inch TV. As shown below, the “typical power consumption” is 82 watts, but the “maximum power consumption” is 255 watts, more than three times higher. The monitor used in Dolby’s HDR demos is liquid cooled.

All of the above are issues that need to be worked out, from standards and recommended practices to aesthetic decisions. And working such issues out is not really new. Consider those motion artifacts. Even old editions of the American Cinematographer Manual included tables of “35mm Camera Recommended Panning Speeds.” As for power, old TV sets from the era of tube-based circuitry used more power even with smaller and dimmer pictures. But then there’s the bottom line, the lowest light level of the dynamic range.

Consider the HDR portion of the requirements for the “Ultra HD Premium” logo shown above that Samsung TV. According to a UHD Alliance press release on January 4, to get the designation, aside from double HD resolution in both the horizontal and vertical directions and some other characteristics, a TV must conform to the SMPTE ST2084 electro-optic transfer function and must offer “a combination of peak brightness and black level either more than 1000 nits peak brightness and less than 0.05 nits black level or more than 540 nits peak brightness and less than 0.0005 nits black level.” The latter is a ratio of more than a million to one.

Consider the HDR portion of the requirements for the “Ultra HD Premium” logo shown above that Samsung TV. According to a UHD Alliance press release on January 4, to get the designation, aside from double HD resolution in both the horizontal and vertical directions and some other characteristics, a TV must conform to the SMPTE ST2084 electro-optic transfer function and must offer “a combination of peak brightness and black level either more than 1000 nits peak brightness and less than 0.05 nits black level or more than 540 nits peak brightness and less than 0.0005 nits black level.” The latter is a ratio of more than a million to one.

The high end of those ranges is beyond most current video displays but achieved by some. Again, new equipment might be required but not new technology. And the bottom end seems achievable, too. Turn off a TV, and it emits no light. Manufacturers just need to be able to have black pixels pretty close to “off.”

What the viewer sees, however, is a different matter. At right is an image of a TV set posted by Ma8thew and used in the Wikipedia page “Technology of television.” The TV set appears to be off, but a lot of light can be seen on its screen. The light is reflected off the screen from ambient light in the room. Cedric Demers posted “Reflections of 2015 TVs” on RTINGS.com. The lowest reflection listed was 0.4%, the highest was 1.9%. Of course, that’s between 0.4% and 1.9% of the light hitting the TV set. How much light is that?

What the viewer sees, however, is a different matter. At right is an image of a TV set posted by Ma8thew and used in the Wikipedia page “Technology of television.” The TV set appears to be off, but a lot of light can be seen on its screen. The light is reflected off the screen from ambient light in the room. Cedric Demers posted “Reflections of 2015 TVs” on RTINGS.com. The lowest reflection listed was 0.4%, the highest was 1.9%. Of course, that’s between 0.4% and 1.9% of the light hitting the TV set. How much light is that?

At left is a portion of an image of the TV room of a luxury vacation rental in France, listed on IHA holiday ads. The television set is off. It shows a bright reflected view of the outdoors. It looks very nice outside — possibly too nice to stay in and watch TV. But, if one were watching TV, presumably one would draw the drapes closed. If the windows were thus completely blocked off and not a single lamp were on in the room, would that be dark enough to appreciate the 0.0005-nit black level of an Ultra HD Premium HDR TV?

At left is a portion of an image of the TV room of a luxury vacation rental in France, listed on IHA holiday ads. The television set is off. It shows a bright reflected view of the outdoors. It looks very nice outside — possibly too nice to stay in and watch TV. But, if one were watching TV, presumably one would draw the drapes closed. If the windows were thus completely blocked off and not a single lamp were on in the room, would that be dark enough to appreciate the 0.0005-nit black level of an Ultra HD Premium HDR TV?

It would probably not be. What’s the problem? For one thing, the viewer(s).

Consider a movie-theater auditorium. When the movie comes on, all the lights (except exit lights) go off. The walls, floor, and seats are typically made of dark, non-reflective materials. Scientists from the stereoscopic-3D exhibition company RealD measured the reflectivity of auditorium finishes (walls and carpet), seating, and audiences and concluded that the last were the biggest contributors to light reflected back to the screen (especially when they wear white T-shirts). Discussing the research at an HDR session in a cinema auditorium at last fall’s International Broadcasting Convention (IBC), RealD senior vice president Peter Ludé joked that for maximum contrast movies should be projected without audiences.

Ludé went a step further. Reflections off the audiences are problematic only when there is sufficient light on the screen. So, he joked again, for ideal HDR results, the screen should be black. At right is an image shot during a Sony-arranged live 4K screening of the 2014 World Cup at the Westfield Vue cinema in London. The ceiling, the walls, the floor, and the audience are all visible because of light coming off the screen and being reflected.

Ludé went a step further. Reflections off the audiences are problematic only when there is sufficient light on the screen. So, he joked again, for ideal HDR results, the screen should be black. At right is an image shot during a Sony-arranged live 4K screening of the 2014 World Cup at the Westfield Vue cinema in London. The ceiling, the walls, the floor, and the audience are all visible because of light coming off the screen and being reflected.

Now consider a home with an Ultra HD Premium TV emitting 540 nits. The light hits a viewer. If the viewer’s skin reflects just 1% of the light back to the screen and the screen reflects just 0.4% of that back to the viewer, there could be 0.0216 nits of undesired light on a black pixel (it’s more complicated because the intensity falls with the square of the distances involved but increases with the areas emitting or reflecting). That’s not a lot, but it’s still 43.2 times greater than 0.0005 nits.

A million-to-one contrast ratio? Maybe. But maybe not if there’s a viewer in the room.

Tags: 4K, American Cinematographer Manual, ARRIS, black level, HD, HDR, HFR, High-Dynamic Range, HPA Tech Retreat, hue shift, motion artifacts, Peter Lude, RealD, reflection, Sean McCarthy, SMPTE, UHD Alliance, Ultra HD Premium, WCG, Xensium,

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

The comments are closed.