The Alternatives

At next month’s SMPTE/NAB Technology Summit on Cinema in Las Vegas, one session will be devoted to “Alternative Content.” What’s that? It’s complicated.

One hundred years ago, the 1912 World Series was quite an event. In the history of baseball, it was the only best-of-seven World Series to have eight games. But the picture above, from the excellent Shorpy site, http://www.shorpy.com/node/4733, is confusing.

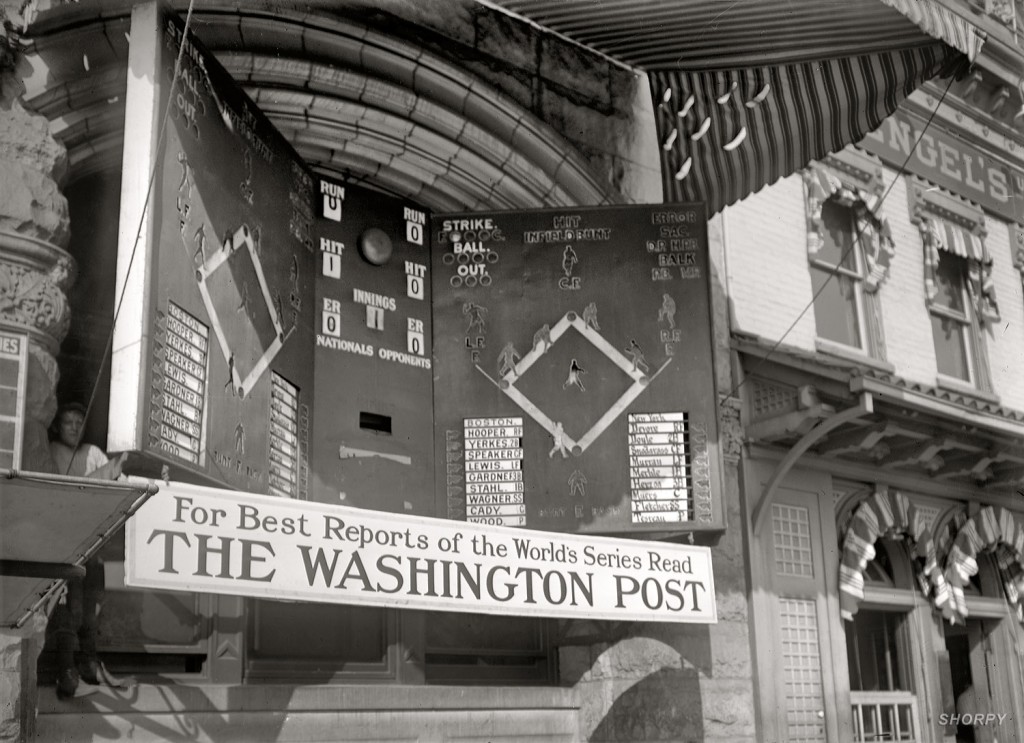

The World Series was a contest between the Boston Red Sox and the New York Giants, and it was played, as might be expected, at Fenway Park and the Polo Grounds, respectively, in those cities. But the crowd above was in Washington, D.C. What were they looking at?

They were looking at a scoreboard (http://www.shorpy.com/node/4734), shown above. If that seems ridiculous, consider 1912. There was no Internet. There were no TV or radio sportscasts. Just about the only way to keep track of the game was to hang around a newspaper office, where reports received by telegraph would be posted.

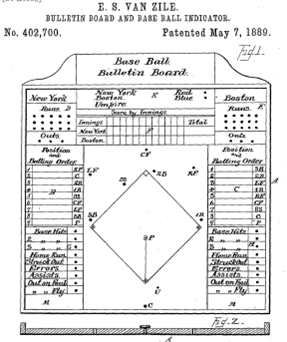

Even in 1912, it was a pretty old idea. The New York State Oswego Daily Times reported on May 23, 1876 about “a group of Syracusans” keeping track of an away game by gathering “around the baseball bulletin.” In 1888, Edward Sims Van Zile filed a patent application for a “Bulletin-Board and Base-Ball Indicator”

Even in 1912, it was a pretty old idea. The New York State Oswego Daily Times reported on May 23, 1876 about “a group of Syracusans” keeping track of an away game by gathering “around the baseball bulletin.” In 1888, Edward Sims Van Zile filed a patent application for a “Bulletin-Board and Base-Ball Indicator”

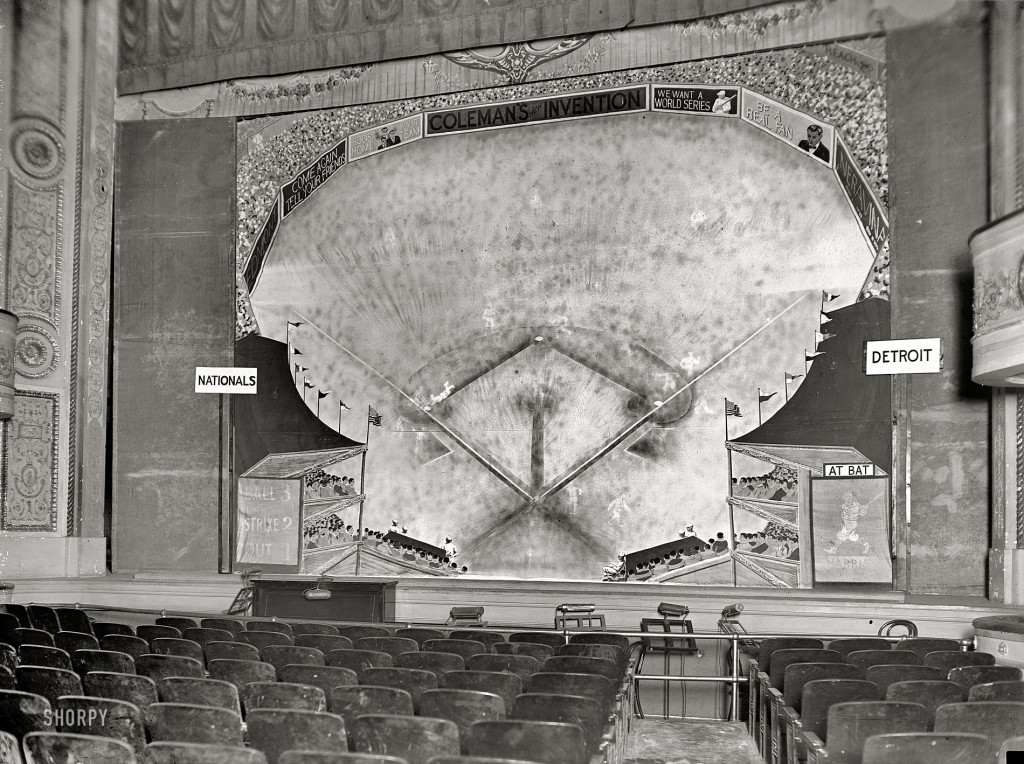

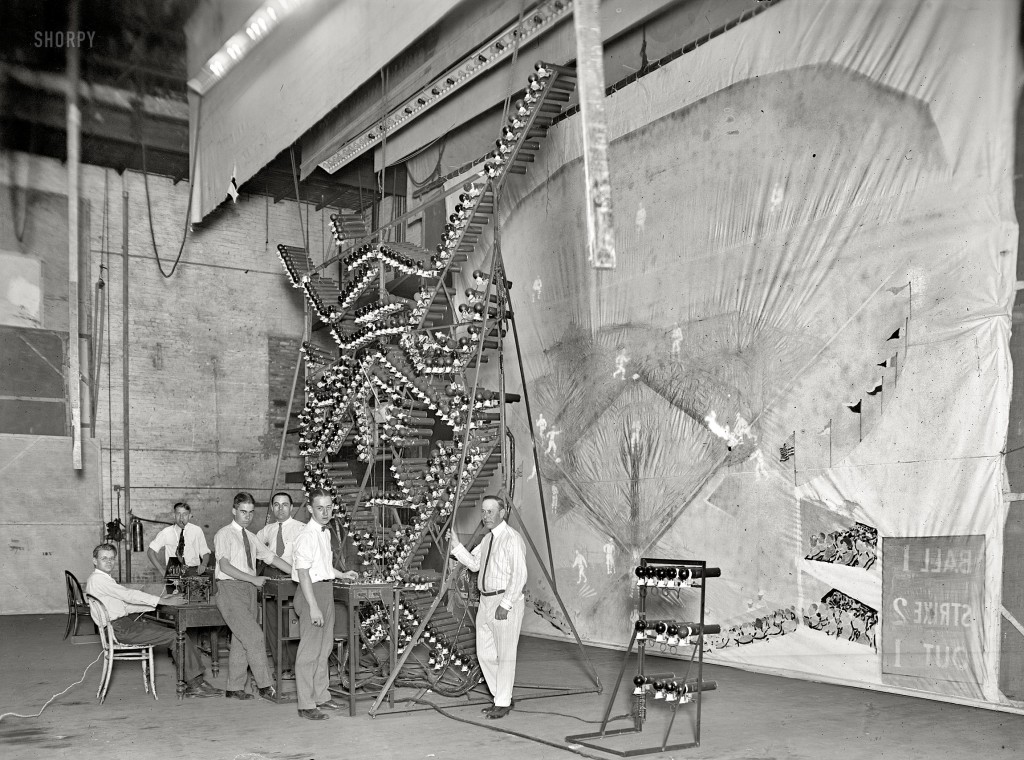

By 1895, the fans had moved indoors. Frank Chapman’s “Automatic Baseball by Electricity” opened at Palmer’s Theatre in New York City that July. According to a lengthy report about the apparatus in the August 7 issue of The Electrical Engineer, the stage was turned into a ball park. “All the players have their proper positions on the big field, and are represented by dummy marionettes, true to the life and about 3 feet high,” moving according to the action being telegraphed from the real game. In 1907, Buffalo’s Garden Theatre offered an “electric baseball diagram.” In 1908, it was the 1750-sear Gotham Theatre in New York City.

Thanks to Shorpy, again (http://www.shorpy.com/node/8283), above is a view of what audiences at Washington’s National Theater saw of the Coleman Life-Like Scoreboard in 1924 (some version had been in use there since 1913, before that a Jackson scoreboard, and before that a Rodier). Below (http://www.shorpy.com/node/8285) is what it looked like backstage with its five operators.

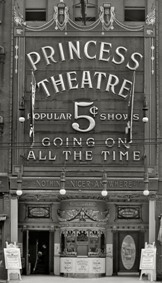

When people went to a theater in 1909 to watch a game via the Rodier Electric Baseball Game Reproducer (“which set Atlantic City wild”), they paid admission prices of 25 and 50 cents. The same year, as the photo at left, taken in Detroit, clearly indicates (http://www.shorpy.com/node/9474), the admission price for a typical movie theater was just five cents (thus the name Harry Davis and John Harris gave in 1905 to the first theater dedicated to showing nothing but movies, Nickelodeon).

When people went to a theater in 1909 to watch a game via the Rodier Electric Baseball Game Reproducer (“which set Atlantic City wild”), they paid admission prices of 25 and 50 cents. The same year, as the photo at left, taken in Detroit, clearly indicates (http://www.shorpy.com/node/9474), the admission price for a typical movie theater was just five cents (thus the name Harry Davis and John Harris gave in 1905 to the first theater dedicated to showing nothing but movies, Nickelodeon).

Not only could theaters charge five-to-ten times the price of a movie to provide some sort of community access to a remote event, but they filled up, too. In Washington, D.C. in 1914, viewers could “attend” different baseball games at the Bijou, Columbia, Cosmos, Gayety, Keith’s, National, and Poli’s theaters, and, if one of those was busy with a play, the equipment was moved into an armory. In New York, the Coleman Life-Like Scoreboard was also set up in an armory, as well as in Madison Square Garden.

The previous post here (on theatrical television) noted that opera was proposed for transmission to theaters in 1877 and has been carried live to ball parks (http://www.schubincafe.com/2012/03/21/getting-the-big-picture/). In 1914, the opposite occurred. The Providence Opera House installed a Coleman Life-Like Scoreboard for baseball-game viewers (in 1931, the Tuscon Opera House was still offering viewers the opportunity to “watch” the World Series on a Playograph). And, in the same year of 1914, Archibald Low demonstrated a crude form of television in London.

The previous post here (on theatrical television) noted that opera was proposed for transmission to theaters in 1877 and has been carried live to ball parks (http://www.schubincafe.com/2012/03/21/getting-the-big-picture/). In 1914, the opposite occurred. The Providence Opera House installed a Coleman Life-Like Scoreboard for baseball-game viewers (in 1931, the Tuscon Opera House was still offering viewers the opportunity to “watch” the World Series on a Playograph). And, in the same year of 1914, Archibald Low demonstrated a crude form of television in London.

In 1925, Low published a book called The Future. In that book, he described (and showed an image of) viewers in London watching car races transmitted from Australia live (right).

In 1925, Low published a book called The Future. In that book, he described (and showed an image of) viewers in London watching car races transmitted from Australia live (right).

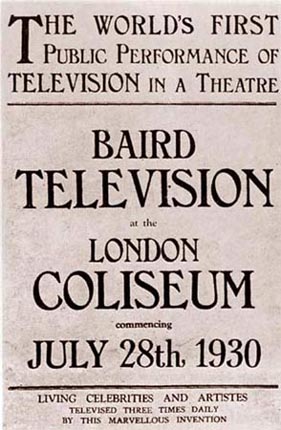

After theatrical television systems became reality, audiences flocked to see those. And just what did they go to see? “Television,” as the poster at left indicates. Even as late as 1948, Alfred N. Goldsmith wrote in the Journal of the Society of Motion-Picture Engineers, “Television pictures in theaters will, initially, at least, have the strong appeal of novelty.”

The first content to be described as other than just “television” was the Epsom Derby in 1932, followed by an international transmission that brought a Danish film star’s image home from London. In 1936, the Olympic Games in Berlin were seen in television-viewing theaters like the one shown at right. In 1941, theatrical viewers saw live boxing and (finally) baseball; in 1952, they saw their first live opera, a Metropolitan Opera production of Carmen, seen in 31 cinemas in 27 cities (below).

The first content to be described as other than just “television” was the Epsom Derby in 1932, followed by an international transmission that brought a Danish film star’s image home from London. In 1936, the Olympic Games in Berlin were seen in television-viewing theaters like the one shown at right. In 1941, theatrical viewers saw live boxing and (finally) baseball; in 1952, they saw their first live opera, a Metropolitan Opera production of Carmen, seen in 31 cinemas in 27 cities (below).

Plays, football, basketball, symphony concerts, and even Presidential addresses were soon added. Results seemed, initially at least, very promising. U.S. News & World Report noted in 1949, “By 1952, most important theaters are expected to be equipped with television screens.” The Billboard reported on February 9, 1952 about a recent boxing match sent to theaters. “The State-Lake Theater in Chicago was the scene of a near riot, with disappointed people in the long line smashing down the doors in an effort to see the showing.”

When Life magazine looked at the field on January 5, 1953, however, less than a year later (when theatrical television was sometimes called closed-circuit TV), the report was not as glowing. Considering a carpet convention replaced by theatrical television (below), they quoted an unhappy “Midwest rug dealer” who missed the face-to-face get-together. “How else can I get away from my wife for five days?”

When Life magazine looked at the field on January 5, 1953, however, less than a year later (when theatrical television was sometimes called closed-circuit TV), the report was not as glowing. Considering a carpet convention replaced by theatrical television (below), they quoted an unhappy “Midwest rug dealer” who missed the face-to-face get-together. “How else can I get away from my wife for five days?”

This was their description of the success of the opera transmission. “Like most others, this Denver theater was not sold out. Many of them lost money on the opera.” And their comments on the technical quality were even worse. “The moviegoers… heard the music distorted, often sounding like a worn-out record. Faces of singers became ghostly blobs, and their figures were so elongated that one critic saw ‘people resembling overripe bananas.’ Color was sadly missed.” The carpet convention, too, “suffered from poor picture images and lack of color.”

This was their description of the success of the opera transmission. “Like most others, this Denver theater was not sold out. Many of them lost money on the opera.” And their comments on the technical quality were even worse. “The moviegoers… heard the music distorted, often sounding like a worn-out record. Faces of singers became ghostly blobs, and their figures were so elongated that one critic saw ‘people resembling overripe bananas.’ Color was sadly missed.” The carpet convention, too, “suffered from poor picture images and lack of color.”

Perhaps surprisingly, then, the comment cards filled out by viewers, available for inspection at the Metropolitan Opera Archives, are almost uniformly positive, even at a theater that was briefly accidentally switched to TV-network programming (TV stations had to forego their network feeds to allow the opera transmission through). Why? Possibly crowd mentality and cognitive dissonance. In a theater, if no one else complains, why should you? As for the dissonance, if you pay a lot for a ticket (up to about $65 in today’s money), dress up, hire a babysitter, travel to the theater, and don’t like the show, you were stupid to expend so much time, money, and effort, so maybe it wasn’t so bad.

Perhaps surprisingly, then, the comment cards filled out by viewers, available for inspection at the Metropolitan Opera Archives, are almost uniformly positive, even at a theater that was briefly accidentally switched to TV-network programming (TV stations had to forego their network feeds to allow the opera transmission through). Why? Possibly crowd mentality and cognitive dissonance. In a theater, if no one else complains, why should you? As for the dissonance, if you pay a lot for a ticket (up to about $65 in today’s money), dress up, hire a babysitter, travel to the theater, and don’t like the show, you were stupid to expend so much time, money, and effort, so maybe it wasn’t so bad.

Regarding the financial failure, it was of its time. In 1952, there were about 2.7 billion movie tickets sold in the U.S.; in 2011, it was less than 1.3 billion. At the same time, the U.S. population grew from 158 million to 312 million, so people went to about four times as many movies back then. And movie theaters were larger, many with more seats than the opera house. If the theaters could fill those seats with movies and not with opera, then the latter was a failure.

Whatever the reason, theatrical television in the 1950s (like that era’s 3D movies) was not a lasting success. Movie studios dropped plans, and few movie theaters were equipped. When Theater Network Television, the first and largest theatrical television distributor, transmitted its 75th event, in 1954, a General Motors celebration of the production of their 50-millionth vehicle, the viewing venues included Carnegie Hall but also conference rooms in 52 hotels.

Today is a different era. Instead of being called theatrical television or closed circuit, the field is now “alternative content,” cinemas are equipped for non-film-based projection, and, perhaps due to its institutional nature and fan base, opera has become the number-one alternative content worldwide.

Today is a different era. Instead of being called theatrical television or closed circuit, the field is now “alternative content,” cinemas are equipped for non-film-based projection, and, perhaps due to its institutional nature and fan base, opera has become the number-one alternative content worldwide.

What is alternative content? Consider the matrix at left from the web site of BY EXPERIENCE HD, which calls itself “Pioneers of Global Live Cinema Events.” It includes operas, plays, radio shows, talks (including a talk about a TV series), concerts ranging from classical to rock, a documentary, and a college-choir holiday performance probably aimed primarily at the school’s alumni (http://www.byexperience.net/).

That’s just one producer/distributor. Others provide marching bands, ballet, church services, sports, political and economic events, children’s shows, instruction, charity events, and even game-playing, some in stereoscopic 3D.

Strangely, even movies can be alternative content. They just have to be tied to specific moments: anniversaries of classics, reminders of what preceded new sequels, and previews.

The key is that, whatever else the alternative content might be, it must be an event. Unfortunately, non-alternative content (better known as regular movies) does not share the event nature. Cinema personnel are, therefore, not accustomed to dealing with such issues as signal reception (at right, brushing snow out of a satellite dish above a cinema in Erie, Pennsylvania) or even noticing when a live event has ended, which is why the mostly white image shown below remains on screen for the last ten minutes of each Metropolitan Opera cinema transmission; it provides exit lighting.

The key is that, whatever else the alternative content might be, it must be an event. Unfortunately, non-alternative content (better known as regular movies) does not share the event nature. Cinema personnel are, therefore, not accustomed to dealing with such issues as signal reception (at right, brushing snow out of a satellite dish above a cinema in Erie, Pennsylvania) or even noticing when a live event has ended, which is why the mostly white image shown below remains on screen for the last ten minutes of each Metropolitan Opera cinema transmission; it provides exit lighting.

The economics of alternative content have also changed since the 1950s. According to published figures, The Metropolitan Opera: Live in HD has finished as high as ninth in weekend U.S. movie theatrical box office grosses. That can seem spectacular, given that there was a single showing of the opera vs. three days of continuous movie showings. Due to those continuous and ongoing showings (beyond the weekend), however, the movies continue to earn theatrical revenues, whereas the opera (except for an “encore” presentation) doesn’t. An opera that ranked ninth in its live weekend could fall to near 200th in revenue for the year.

On the other hand, alternative content doesn’t necessarily have to make a profit for its producer. If it increases exposure, donations, voter turnout, opera-house attendance, community outreach, etc., it can serve its purpose.

Exhibitors (movie-theaters) do need justification to provide auditoriums, however, which is another reason why alternative content is often priced higher than movies — and scheduled for low-movie-attendance times. An opera that starts at 9 am on the U.S. west coast and lasts for hours — with intermissions — can not only fill an otherwise empty cinema but also provide exceptional business for its concession stand, as the photo above left indicates (a portion of a larger image that appeared in The New York Times on January 1, 2007, shot by J. Emilio Flores in a Burbank, California cinema during the Metropolitan Opera’s The Magic Flute, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/01/arts/music/01scre.html).

Exhibitors (movie-theaters) do need justification to provide auditoriums, however, which is another reason why alternative content is often priced higher than movies — and scheduled for low-movie-attendance times. An opera that starts at 9 am on the U.S. west coast and lasts for hours — with intermissions — can not only fill an otherwise empty cinema but also provide exceptional business for its concession stand, as the photo above left indicates (a portion of a larger image that appeared in The New York Times on January 1, 2007, shot by J. Emilio Flores in a Burbank, California cinema during the Metropolitan Opera’s The Magic Flute, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/01/arts/music/01scre.html).

Of course, as in the 1950s, this is a challenging era for movie exhibitors. With television’s household penetration increasing back then, the movie business turned to stereoscopic 3D and higher-resolution formats. Today, with HD home-theater penetration increasing, the movie business is turning to, well, stereoscopic 3D and higher-resolution (4K) formats. And with sports arenas and arts centers also equipped to show HD images, alternative content can move to alternative venues, like the AT&T Park ball field, shown at right with a live San Francisco Opera feed of Lucia di Lammermoor (http://blog.echovar.com/?p=423).

Of course, as in the 1950s, this is a challenging era for movie exhibitors. With television’s household penetration increasing back then, the movie business turned to stereoscopic 3D and higher-resolution formats. Today, with HD home-theater penetration increasing, the movie business is turning to, well, stereoscopic 3D and higher-resolution (4K) formats. And with sports arenas and arts centers also equipped to show HD images, alternative content can move to alternative venues, like the AT&T Park ball field, shown at right with a live San Francisco Opera feed of Lucia di Lammermoor (http://blog.echovar.com/?p=423).

Though this post has covered events in the U.S., alternative content for cinema is a global phenomenon (pre-Avatar, there was even a live 3D opera from France). Here’s a link to The EDCF Guide to ALTERNATIVE CONTENT in Digital Cinema from the European Digital Cinema Forum, published in September 2008 (it’s also popular in Asia, Africa, Australia, and the rest of the Americas): http://www.edcf.net/edcf_docs/edcf_alt_content_for_dcinema.pdf

Don’t like the movie business? Consider the alternatives.

Tags: alternative content, Archibald Low, ballpark, baseball, BY EXPERIENCE, closed-circuit, Coleman Life-Like Scoreboard, John Logie Baird, Metropolitan Opera, Opera, Technology Summit on Cinema, theatrical television,

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

The comments are closed.