Live From FIFA Women’s World Cup: FIFA’s Florin Mitu, HBS’s Stefan Wistuba Discuss Groundbreaking Workflows

Live coverage is produced from a hub in Sydney; non-live content, from London

Story Highlights

The production philosophy that FIFA and HBS have embraced for the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup in Australia and New Zealand raises the bar when it comes to new concepts in remote production. It is the largest and most prestigious event on which the teams producing the live match coverage are based not at the stadiums but at a central production hub. And it could be a game-changer.

IP flypack capture kits at each of the 10 stadiums transport the audio and video signals to the hub. At that hub, in Sydney, are four main galleries where production teams that historically would work in a truck in a car park go about their business of producing world-class World Cup coverage.

Florin Mitu, head of broadcast production, FIFA, and Stefan Wistuba, project director, HBS, sat down with SVG Co-Executive Director Ken Kerschbaumer at the Women’s World Cup IBC in Sydney Olympic Park to discuss the new workflows, IBC operations, and much more.

This year, FIFA and HBS have a new philosophy for production: the match production teams are working in galleries at a hub here in Sydney instead of in trucks at the stadium. How have things been going?

Mitu: From a FIFA perspective, I can say we were looking forward to doing something like this setup with the remote production. Sustainability is a big factor in everything that we are doing and what we are planning going forward, and this has allowed us to see in the real world how it would work.

In general, we can say it works well. It obviously involves some challenges in the planning phases and at the start of the tournament until it started working like a well-oiled mechanism. But we’re very happy so far.

It’s more sustainable, but what are the benefits you have seen with the production teams?

Mitu: My feeling is that it creates a team atmosphere that also achieves the consistency we’re so keen to have at the World Cup. Everybody is in the same building and working in different galleries, but they also stay in the same hotel so it’s easier for them to talk to each other and exchange experiences and learnings. Of course, there is the downside that they never see the cameramen, but, nevertheless, everyone has managed to adapt to the setup, which is working well.

Wistuba: I agree. We took the approach that, in all areas of the event, we wanted to do things differently. Not just the live side of the production but also the non–live-content-production side, which is being done out of a hub in the UK and in a streamlined way from the IBC.

In every aspect, we want to be more sustainable and challenge ourselves. We had five production teams working across 10 stadiums, so how does that all work from a centralized perspective? It worked out well, but the setup phase was demanding as we had not only to deal with the live side of rehearsals and checks but also to integrate all the other sides from FIFA, like FIFA Football Technology and Data and FIFA Infotainment. A big number of feeds had to be routed properly between the live hub, IBC, and non-live hub working in a different time zone.

The first week was tough. Even with great facilities like we have here, nothing is ever plug-and-play. You work through a lot of long nights getting everything resolved. The goal is to have a remote production where the viewers don’t notice a difference from a cutting perspective or replay perspective, and that has been achieved.

I also think the production teams feel good being in the remote facility. They have a comfortable environment to work in, and things have settled down, and they are in a groove. They’re not traveling; [they are] able to walk to the live hub. They’re rested and have been able to produce a lot more games individually, compared with previous tournament rotations. If they had to travel, we would need as many as 10 production teams for this event.

We’re also using a lot of the local Australian and New Zealand camera operators and teams and marrying them up with the international teams, which has worked out very well in terms of quality, leaving a legacy, and reducing the carbon footprint.

And a lot of those local production people have been working this way for a few years so I am sure that must have made you more comfortable with wanting to work this way.

Wistuba: One hundred percent.

Mitu: We employed four directors who have all done remote productions at some time, not just during the time of COVID. The only one who had not is Sebastian Von Freyberg from Germany, and he has felt very, very comfortable working remotely.

Another important step we, together with HBS, had undertaken was to bring in three new directors to the FIFA World Cup setup. Jamie Oakford from the UK and Freyberg from Germany have done World Cups before, but Gemma Knight from the UK, Angus Millar from Australia, and Danny Melger from Netherlands are new to the World Cup, and we’re very comfortable with their work. It’s a very important game for FIFA to have new blood on board. Back to working remotely, the fact that they can look to Sebastian and Jamie and work with them helps their development as FIFA World Cup directors.

How are camera meetings and production-team meetings held?

Wistuba: I think it’s more than just camera meetings on the day of the match; it’s also briefing the ops, and especially the local ops that haven’t been working with international production teams. The five production teams have different ways of working, and they differ in their ways of using cameras as well. We needed to get that message across to the teams, and that required the directors to put more effort into that with phone calls, teams calls, and actual briefings with the personnel onsite at a stadium via comms. We also have set times when everybody must be on the cans, and we used little gimmicks like a return feed from a video camera in the hub so those at the venue could see the director.

In the end, it’s about communication and speaking to the production team clearly so they know what you need from them. And everyone has reacted and adapted very well.

There are two types of facilities in use: two stadiums have trucks, and some just have a flypack. Do they operate differently?

Wistuba: No, there’s no difference in terms of technology: it’s just where the the technology lives. The fly kits are installed in cabins that have capture kits that the cameras are connected to. In Australia, we are using two trucks, but they are used only as a capture kit. When transmitting camera signals, there is not a difference between the flypacks and trucks other than that the trucks have wheels.

Who else is at the venue on a match day? Obviously, the camera people are there, but who else? And who manages things if they go wrong?

Wistuba: First, all the people that work in the gallery are not there. And all the shaders are at the hub instead of onsite, which is quite new, even to the Australian market.

Onsite, we have a senior guarantee video and audio, video and audio assistants, camera ops, floor manager, and riggers. All the technical support that you would have on a normal OB would be onsite as well. And we rely heavily on floor managers, [who] become the eyes and ears of the director.

Mitu: Apart from Angus, who is local, none of the other directors have been to the venues, maybe except for those in Sydney.

Wistuba: It’s definitely challenging for the directors when they work a match in Melbourne remotely one day and then a match in Hamilton the next. It’s a completely different stadium, and they need to get their head around what they can and can’t do with the cameras. That takes more time. It’s not impossible, but, in the end, you rely on your camera ops to get the best shots.

Are other aspects of the FIFA operations being done remotely as in Qatar for the 2022 World Cup?

Mitu: We’re doing the infotainment remotely from the IBC with four galleries, and that is something we did at the previous World Cup in Qatar. We have the VAR at the IBC, although all feeds first go to the hub and then come to the IBC.

Wistuba: And, from the IBC, the VAR camera feed goes back to the hub, where it is integrated; we have four VAR cameras that are integrated into the feed.

Mitu: Speaking about our VAR coverage, at this Women’s World Cup, the match officials announce the decisions following VAR reviews. Viewers in the stadium and back home can now hear the referees announcing and explaining their decisions. We are thankful for the great cooperation we had with our colleagues from the Refereeing and Football Technology and Data teams in implementing this innovation.

There are only a handful of rightsholders onsite. Was that in line with your expectations?

Mitu: Australia is very far away from a lot of other territories in the world, and it was to be expected that many broadcasters will do remote from their home countries rather than have a significant base here. Catering to the needs of those who are at their home base meant we needed to provide them with adequate content and make sure once again that the FIFA MAX server is accessible from anywhere in the world, not only at the IBC.

What other kind of content are you providing?

Mitu: We have 32 FIFA TV Team Crews embedded with the teams; there’s a lot of material being shot and produced, which is very, very useful for any rightsholders, wherever they are: for instance, exclusive interviews with the players, the head coach, and backroom staff in the build-up to each match, as well as behind-the-scenes filming and footage from any extracurricular events that the teams undertake, as well as training sessions and press conferences. On match days, each crew will be in the stadium to support the HBS coverage by providing further content, such as pre-match and post-match interviews, fan color, match iso, and post-match dressing-room filming.

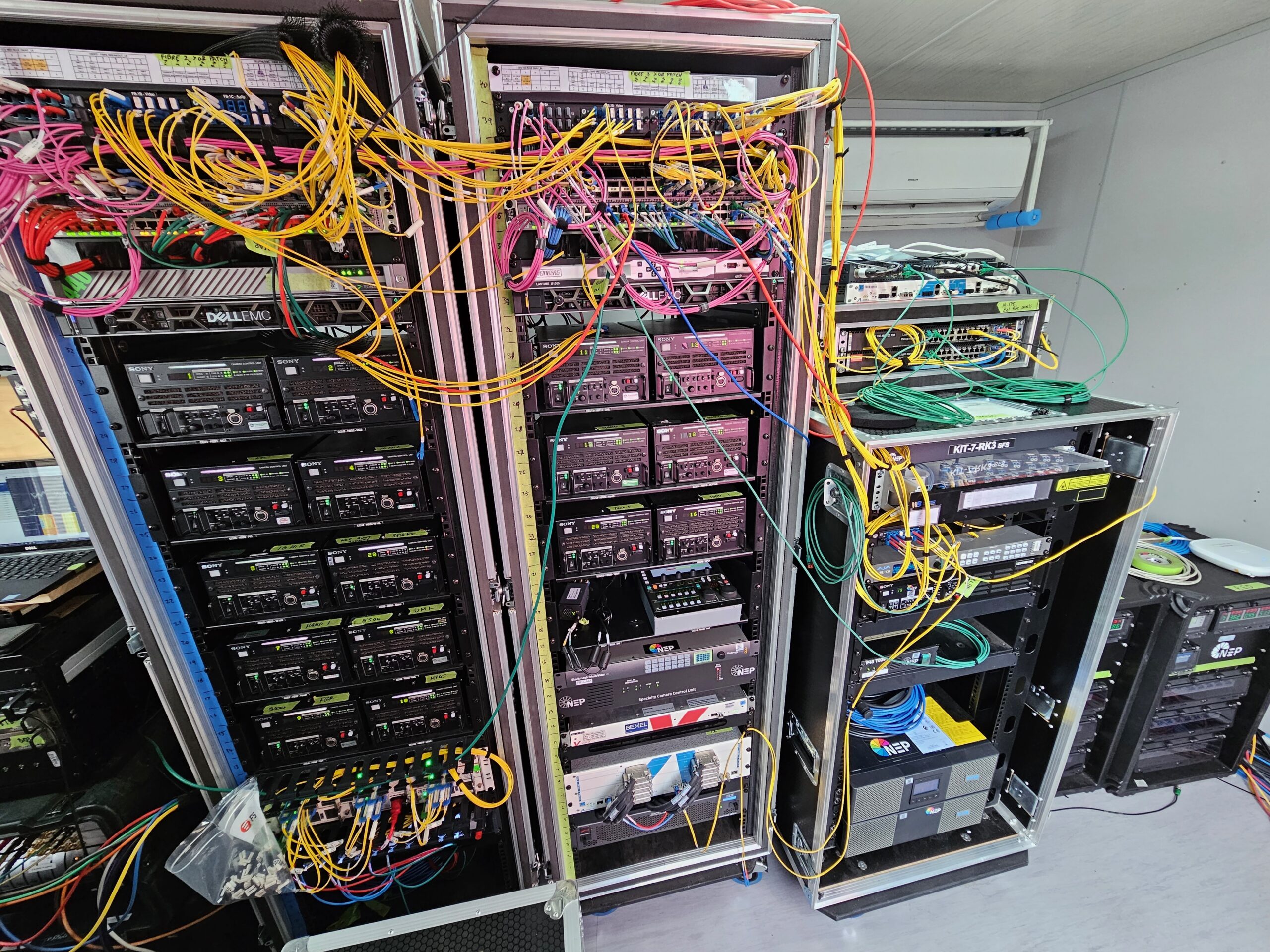

This flypack at Allianz Stadium in suburban Sydney is the main technical facility onsite. It is connected to a gallery at the World Cup production hub.

Wistuba: Rightsholders rely more and more on that content. On the non-live side, it’s worth mentioning the non-live hub that we have in London. It’s quite a big operation with postproduction, media management, server ingest, and management and logging taking place in the non-live hub. We used to have to bring all that equipment and personnel to the World Cup location, situated at the IBC.

They produce critical near-live highlights and digital edits, while, here at the IBC, we are doing quite a lot of feature productions because those production teams need to be in touch with the teams on the ground. One big challenge has been the time-zone differences; they’re working night shifts in London to align with us.

At the IBC, we have six edit suites for features production, but, instead of high-end edit suites, they are using laptops, which is a simpler approach. In addition, FIFA Studios have five traditional edit suites.

The digital side is always picking up, so the value of having so many people covering the teams is that the access has been immense and creates great content. Key is getting everything coordinated and controlled so that FIFA can benefit from the unique opportunity of getting close to the teams. We have 18 digital-content creators spread across all the host cities as well, capturing content on mobile devices on match days at the stadium, and, between match days, they cover the teams.

Can you talk about planning both the Men’s World Cup in Qatar last year and this World Cup at the same time?

Mitu: We were working on both at the same time, and both FIFA and HBS had dedicated teams on each as well as people working on both. We have been very fortunate to have a strong broadcast team within the FIFA subsidiary here in Australia and New Zealand who have supported tremendously the event planning and delivery. The other challenge was, it was still COVID times during the initial planning phase. Teams flying here had to quarantine before they could visit stadiums, and then they would have to quarantine again when returning to Europe.

Everyone here and there had to adjust to a different way of communicating, which meant early-morning meetings for us in Europe and late-evening meetings for those here on a daily basis.

Wistuba: We’ve gone from an IBC to [another] IBC, with very little time in between. It’s obviously a bit more stressful on everybody, but it’s working out. And every event builds on the previous event, so we have been able to bring things that were introduced in Qatar, like the use of the semi-automatic offside lines and shooting cine-style or integrating the connected ball graphics and dressing-room coverage. That was all new six months ago, and you can already see those things getting smoother.

Were the IP workflows a little smoother here than in Qatar?

Wistuba: We went to an existing IP facility here, and that was probably the biggest difference; in Qatar, everything needed to be set up. But it’s still challenging on the IP side and during that initial phase and the first two weeks of getting everything up and running: things like getting into the venues, getting to finally see camera signals, and getting those cameras feeds into the right gallery. It all works, but it takes time.

Mitu: And let’s not forget, each director works in a different way, and their gallery setup is different. The directors go into the same galleries one after the other, so there is a lot of preconfiguring time needed.

Wistuba: Once that preconfiguring is done, you have a lot more flexibility with things. But that configuring time is a lot more than just the old SDI workflow, where you connect the cable. In that environment, you just need enough manpower to connect all the cables. But, in IP, the configuring time is the daunting part: there aren’t that many specialists who can do it. You are limited to a group of people who are the brains of the operation, and it means they have long nights.

What do you think will be the legacy of this World Cup? Is this workflow the new way forward? Will the 2026 World Cup be done remotely?

Mitu: I know it’s a cliché that you have to take it one game at a time, but every World Cup has its specifics. The venues in 2026 will be spread across three countries, which is new to a World Cup setup.

But are we going to do remote? There are a lot of reasons we would, but we need to thoroughly assess every facet of it and balance all the pros and cons. For now, we are investigating the telecommunications infrastructure in North America to see what it can offer and what the synergies could be between broadcast-production needs and telco capabilities.

And then there is the question of what is remote. It can be remote from one central point connecting all the venues, or it could be various hubs in various places. And there are the different time zones. But our experience and the learnings from this tournament give us a lot of confidence that we know how to tackle the topic and ultimately reach the right decision.

Wistuba: You have to adapt it to the right infrastructure in a country, look at all aspects of the production and then do a detailed risk planning to see what makes sense. You don’t just do remote because it is a buzzword and everybody says, “Do remote.” It needs to work for the event.

We’ve done elements of remote at many World Cups in the past. Clips compilations, audio surround sound, and Match Day-1 have been done remotely, for example. Elements of remote will be there; it’s just a question of what makes sense.

For now, we’re here in Australia and New Zealand with great people that are enjoying being here, which is a big portion of this. There are really, really good local people, and together with the FIFA team and our international teams, we’re enjoying this event. It’s a nice accomplishment as well.