HBS CEO Dan Miodownik Reflects on Producing Three World Cup Events in One Year

Split ops teams, matching the production philosophy to the event drove efforts

Story Highlights

Last week, the 2023 Rugby World Cup came to a dramatic conclusion in Paris, marking the end of both an exciting tournament for rugby fans and an amazingly busy year for HBS (Host Broadcast Services), which produced three global World Cups: besides the rugby tournament, the 2022 FIFA Men’s World Cup and 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup. HBS CEO Dan Miodownik sat down with SVG in Paris to discuss the accomplishments of the past year, the future of big-time sports production, and the technological changes affecting the way events are produced, distributed, and consumed around the globe.

HBS’s Dan Miodownik: “When you’re doing a World Cup in any sport, you’re talking to many audiences and have to be broader in your appeal.”

How did things go in terms of Rugby World Cup production?

Things went really well. We had a good, strong start, and it just got better and better each week. We also were comfortable with the reliability of our technical platform that supported multiple broadcasters.

Editorially, we wanted to hit the ground running and have consistency from multiple directors as we had an Australian director, an English director, and two French directors. If you look at those countries, they all produce rugby in different ways domestically, so it was important that we ensure consistency while also not beimg so rigid that you can’t identify which director is directing. There was still a bit of the director’s signature, but we had real consistency in how the live cut works, how well it breathes.

How did match production change from 2019 in Japan?

I wouldn’t say there’s a huge change in the principles and the guidelines. When you’re doing a World Cup in any sport, you’re talking to many audiences; you’re not just talking to the purists and the experts. Therefore, you’ve got to be broader in your appeal, but you also have to make sure you don’t alienate your casual or hardcore fan. It can be quite tricky.

Working with World Rugby, we’ve been more consistent this time around with how we’ve applied that philosophy and those guidelines, and we do have a few more toys to play with, such as the cine-style shooting.

Cine-style shooting has been the growth camera of the last few years in big events, and it lends itself in different ways to different sports. The technology has improved by leaps and bounds as the kits are much lighter and much more portable. Personally, I still feel that it can be a bit polarizing at times: you can feel like you’re jumping into something very different to the rest of the live coverage and then jumping back out of it. But that’s part of the learning curve.

In the past 12 months, HBS has tackled the 2022 FIFA Men’s World Cup in Qatar, the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup in Australia, the 2023 Rugby World Cup here in France, and other events. What has that been like?

It has been an incredibly intense 12 months. If you take it from the Men’s World Cup last year to this year and throw in, on top of that, what we call the usual events — LFP Ligue 1 and 2, Roland-Garros, the Gold Cup, Handball World Championships, and the Ice Hockey World Championships — you can start thinking you can have that kind of intensity year in year out, but you can’t. We’ve learned the hard way that you need to address these projects in a slightly different way, which is that you can’t just go from one to the other.

We made the decision, coming out of the Men’s FIFA World Cup, that we were going to split out the teams between things like the FIFA Women’s World Cup and the Rugby World Cup. Of course, some people want to be involved with everything, so that was difficult. But everybody who works in these events knows that, at the end, you do need a bit of time to debrief and rest before you throw yourself into the next event. That’s part of our learning curve over the last two or three years, and it’s something that we’re applying more and more.

What does that mean operationally?

You need to plan way ahead. You’ve got to make sure that your resources give your preparation team the space and time needed as well as reinforcing the team more than we’ve done in the past. Increasingly, these events require more from us technically, editorially, and operationally. So we’ve widened the teams that we have for the preparation, and we’ve widened the pool of people we use for events so that we’re not relying on the same group of people every single time. When you look at the roadmap of the next two, three, four years, you see all those peaks starting to appear, which means you have to have a bigger team, and you have to invest more in people. We need more people, and we’re using more people than we’ve used before.

Since COVID, a lot more workflows have been available to you for producing events. And each of these three major events had a different workflow. How did that develop?

Every major event is different. There are certain principles you can import, but, honestly, you do start from scratch because every event has a different set of challenges and obstacles, regardless of how much it looks the same as the one before.

I discussed this with [OBS Chief Technology Officer Sotiris Salamouris], and they hear the same thing: Oh, it’s the Olympics, and therefore it is the same whether it is in Tokyo or Paris. But, even when events are in our backyard — where we arguably know more about working in France on a big event than most people do — it changes. The challenges are completely different, and those have to do with the type of event, the type of people you’re working with, the geopolitical issues, and all the challenges that come with working in different places. It is easy to think it is simply a copy-and-paste, but it’s just not.

How do you begin that process?

You need to understand what you need to do, what are the things you have to focus on, and what are the priorities. But then you’ve got to start applying that to find out exactly what are the challenges. It could be where the event is or who your clients are; different people have different priorities for the event, whether it’s on technical delivery or operational delivery. They face different problems, whether they’re budgetary or the health and safety rules that they bring, and you’ve got to accommodate all of that into your thinking. It’s not the same as playing in the same stadium every single week.

Was there anything passed down from, say, the Men’s World Cup to the Rugby World Cup?

There are clearly things you learn, and there are common factors, like how you manage the project, and then there are also technical things like the move to IP — which is here to stay. It has significant challenges, and we’ve seen those challenges in all three of the big events of the last 12 months.

IP has the kind of challenges that have really clever people scratching their heads, going, “It has never done that before” or “That’s new” or “I wasn’t expecting that.” How do you mitigate for that? Does it mean you need more commissioning? Does it mean you have to approach things in a slightly different way? I think we’ve learned an incredible amount in that space, in terms of technical platform, how we work with technical partners the likes of NEP, EMG, Gravity, AMP, and EVS. I think they would say the same thing.

Let’s talk about the Women’s World Cup in Australia and New Zealand, where you had a completely remote production. NEP’s Andrews Hub in Sydney played a big part, but how did you transition from Doha to that way of working?

We operated on a proper remote basis in Australia, which we weren’t doing in Doha for the Men’s FIFA World Cup. In Doha, we were doing a portion of it remotely, but the bulk of the main coverage was done at the stadium, and that gives a completely different dynamic to how the directors and their teams are working. We found a whole new set of challenges when you go into the remote world, because it is a different animal. We had galleries being emptied and filled, literally within minutes, from one match to the next. It is a very different way of approaching production as opposed to having discrete venue operations with teams turning up, doing that game, and going away.

I was pleased with the way it went in Australia, partly for the partnership with NEP, because they know how to operate in that environment. [We had] to plan from a distance, then turn up and produce an event of that size. There was a great learning curve that we took from that.

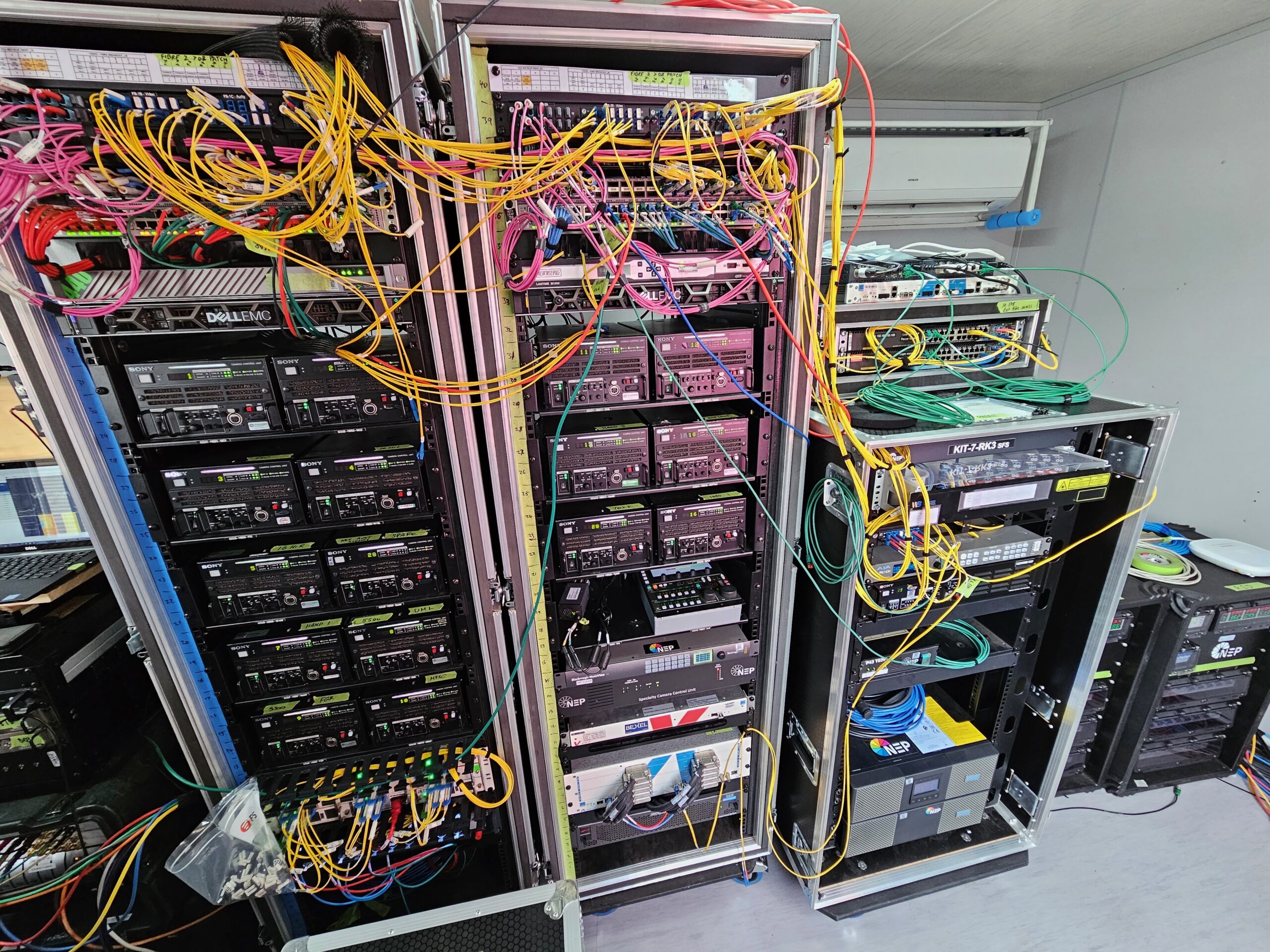

Then we jumped into the Rugby World Cup, which was predominantly trucks and flyaways and kind of back to where we were before the World Cup in Doha. Again, it’s three completely different setups and three completely different sets of challenges, but IP is a consistency in all of them. What we’re learning from that as we go forward is absolutely key.

The technical infrastructure of the TV compounds for the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup was greatly reduced because the production teams operated out of the Andrews Hub in Sydney.

Did the maturity of NEP’s remote workflows in Australia figure into the decision to work remotely?

We went there and did an assessment, we ran an RFP, and we looked at the different options. Some of those are to do with the challenge that you face, be that technical, operational, and, obviously, financial. The decision to go remote was absolutely the right choice.

It also showed that having someone in the country who has mature workflows compared with someone saying “You give me a telco, and I can build you a hub” is unbelievably valuable. I know there are people who can say they can do that, and there’s probably a few that might be able to do that. But it absolutely is not the same thing as someone who has been working in a country for a great number of years and has gone through that pain threshold to the point where they’re not taking risks. You want to take as little risk as you can.

You didn’t feel that you were taking a leap of faith by going remote?

It wasn’t a leap of faith for us. It was trusting in something that was established and believing that it was the right choice. Plus, it gives the added advantage of reducing the number of production teams and, therefore, [means] better consistency in what you’re doing.

Let’s go super macro. The industry at large sees a remote production done that way and says, “This is the future, and this is where all these big events are going to go.” Is that an oversimplification?

Yes. I think it’s a fair statement to make, but I would say two things. One, it’s not always the right solution, because it’s not always mature enough. Sometimes, it’s also not cost-efficient or cost-effective, depending on the level of the event that you’re working on.

I also think you’ve got two races happening here at the moment. You’ve got a race regarding “regular” remote, and you have, at the same time, the race to the complete cloud solution. Traditional remote generally has a big cable in the ground, and people use it to send back signals to make a broadcast signal. But, at the same time, we’ve got this new option, which is complete production in the cloud. That will be a much bigger game-changer, because you are freeing up everything and everyone.

But there are issues and challenges around the cloud. Does it work in the way that you want it to work for your level of production? I think that’s what everyone is looking at now: “This is a category-one event, and this is the risk.” And depending on the value of your event, you will do more or less. We see it now, and we are involved in it for other projects that we work on, where we can do three- to five-camera shoots completely in the cloud. That’s very different to 40-camera coverage of the World Cup Final of a leading sport.

What are the questions around doing a big event in the cloud?

Connectivity is the big question, but you might also question if you will end up with a stronger editorial product as opposed to having people sitting together? Just because your slow-motion operator can be at home in their bedroom doing their job, is that the right way to approach it? There’s quite a lot to play through here. AI might even leapfrog that, anyway, for things like a two- or three-camera show. You may be able to say, “Well, actually, you know what? We don’t need anybody to do that. We just need a machine to do it, because, if the quality threshold is there, trust the machine to do the bare minimum.”

But, if that happens, we will face a skills issue with fewer people involved in the industry, and you have less and less choice. It seems harder to bring people into the industry in some ways because there’s less opportunity, there’s less training. We’re seeing that as a big issue now.

As more and more people on the production are working from more and more locations, that raises the risk of a local outage’s impacting the production.

You start playing the “what happens if” game and end up having to bake in more redundancy than you would have before. That is going to add to cost and complexity. But, again, until you’re at a point where you have extremely consistent reliability of the cloud in the live environment — not postproduction but in the live environment — people are going to be nervous, especially if their product is a category-one product. None of the new ways of working are as consistent as a solution that turns up with a truck.

One big thing that all your events have in common is that the rightsholders need more shoulder-style programming, which means you have more and more ENG crews gathering content at the events.

I was discussing this with Amanda Godson, [head of broadcast and production,] World Rugby, and Florin Mitu, [head of host broadcast production,] FIFA. We are at an interesting point where the maturity of the content plan for the traditional live-broadcast model is at its peak and now there is the introduction of this incredible amount of shoulder content. We have live coverage, which is the sacrosanct part and has to be protected, has to be high-quality and reliable and have the right risk associated to its production.

You have, within that, live feeds giving rightsholders complimentary content. That helps the shoulder content the broadcasters need to create around an event. On top of that, we ask, “What else is going to help rightsholders have more ways to link the matches and event and do all the other things that they want to be able to do?” So you add a media server and additional ENG and feature content.

There is all the content from the matches, and we’re creating this nice library of material that’s living and growing during the tournament and allows the programming part to work.

What about the digital side of things?

I think the biggest and most exciting change we’ve seen in the last two or three years is digital going from being a nice-to-have to something that has grown up. You can think of it as a little brother who is now standing in the room and saying, “Do you know what? I am not saying I’m as valuable as ‘live,’ but I’m becoming as relevant, and I’m becoming relevant for organizations that want to grow, keep, and engage an audience.”

I think we’ll start to see a shift to a lot more digital content and programming targeted at online consumers, because that pot of digital users is growing, like the broadcasters, the digital channels of the federation, or, in some cases, maybe it’s brands associated to the event. You are going to move the dial more on the digital side than you are on the broadcast side, because the broadcast side is mature, while [there is] huge headroom in the digital arena. Yes, there will be live-production enhancements to play with, but no one’s going to massively reinvent the mature, shiny, high-quality, whistle-to-whistle production.

The digital part is huge. Part of it is live, part of it is live around games, like training and influencers; in addition, there is so much more flexibility in the digital part. It’s up to the broadcasters now to figure out what is the best way to treat that digital side, as it’s going to start to punch its weight and it’s going to start to say, “I’m not fighting with you. I’m helping. I’m bringing new viewers and customers. I’m engaging them in different ways. We are making an event, a tournament, a league more relevant to a different audience, in a slightly different way, and not cannibalizing, the broadcast audience.”