How Sound Effects for ‘Monsters Funday Football’ Emulated the Sonic Soul of ‘Monsters, Inc.’

Most effects for the ‘MNF’ altcast were created and saved, then mixed live to air

Story Highlights

Imagine flying a fully loaded 737 airliner for more than three hours in rough weather. Now imagine doing it upside down.

That’s pretty much what it takes to produce an animated, mirrored iteration of a nationally broadcast NFL game, virtually and in real time, with barely a 90-second lag in which to keep up with the IRL action.

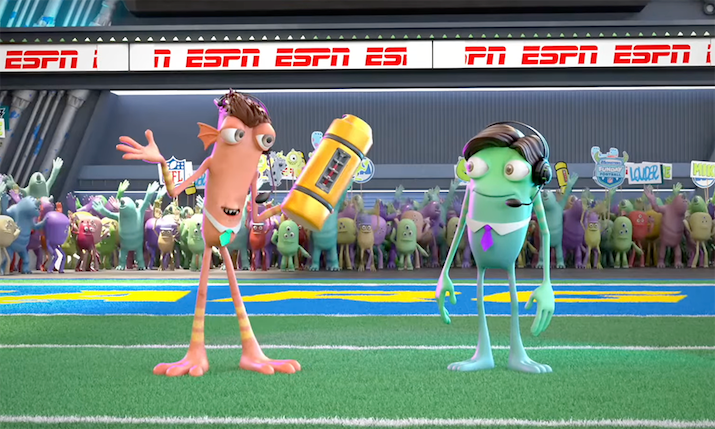

This week’s Monday Night Football approximated that when ESPN’s Monsters Funday Football visited Monstropolis, transforming the night’s Philadelphia Eagles–Los Angeles Chargers matchup into the broadcaster’s most ambitious real-time alternative broadcast yet. Pulled from the Pixar content stable — two earlier iterations of animated NFL shows drew on the Toy Story and The Simpsons IP franchises owned by ESPN parent Disney — the animated production on ESPN2 paced the actual game on the main ESPN channel and ABC.

Analyst Dan Orlovsky (left) and play-by-play man Drew Carter lent their live voices to Funday Football for the second consecutive year.

The game was reimagined on the “Cheer Floor” inside a meticulously crafted virtual Monsters, Inc. factory, blending live NFL tracking data with 30 minutes of new Pixar animation, signature sound bits from the film, and a stadium packed with 5,000 animated monsters roaring along with every play.

Sound Is a Team Sport

Those roars and lots of other SFX were created and mixed by a team working from ESPN’s Bristol, CT, audio facilities. Most of the effects were created by Lead Sound Designer Jason Finberg and mixed live to air by Lead A1 Zac Casey, backed by Audio Guarantee Jason Severance, working under the guidance of David “Sparky” Sparrgrove, senior director, creative animation team, ESPN.

Finberg says he spent considerable time listening to the SFX of the movies, paying particular attention to signature ones such as Sully’s (voiced by John Goodman) plodding footsteps. Those he approximated with a kick drum and some actual footstep effects, topped off with a squish to get what he called the character’s “wet feet.” The Cheer Tank, which measured crowd reactions, was given a kitchen-service bell to ring when it topped off.

“I emulated everything as best as I could, to make it sound as realistic to the movie as I could,” he says, noting that he was still in high school when the original film came out.

Other character sounds, such as the squeals of Archie the Scare Pig, were supplied by Pixar. The voiced characters, like the monocular Mikey Wazoski (Billy Crystal), were prerecorded.

The ambient effects were the most complex. For instance, the crowd cheers were all Finberg himself, chanting into a Neumann TLM 103 microphone multiple times in his Connecticut home studio, adding EQ, compression, and some processing.

“I overdubbed myself 24 different times, different locations around my mic,” he explains. “I literally am just yelling into it in one spot, then I go stand over there and yell, then I go stand over there and yell. I did that for 10 different cheers.”

Rough Mix

Ultimately, more than 500 individual sound clips were numbered, named, and ready from a playout server, when Casey and Severance were ready to mix them live to picture, from one of the audio-control spaces in Bristol, with Casey on the faders and a producer and playout operator managing the sources from the playout deck. (Casey and Severance worked from the audio booth attached to the main control room, while Finberg worked from another audio booth on a different floor.)

“[Producer] Andy Jacobson is basically calling out numbers, just trying to react to the live game,” explains Severance, whose role also included managing communications between each audio location within the facility and with the A1 onsite for the actual MNF game. “For a particular play, he would yell out the number, and the operator has certain kinds of cheers that correspond and are ready to go. A couple times, a character would hold up a first-down sign or a ‘Let’s Go, Chargers’ sign. He had a bank of things that he wanted to go to for that. He’s just basically calling those shots on the fly.”

One of the exciting elements of the altcast production was that ESPN was able to hire actors John Goodman (Sully, left) and Billy Crystal (Mike, right) to reprise their roles by recording up to 30 minutes of original audio to use live throughout the game.

Some additional prerecorded sound was supplied by Beyond Sports, a first for the animated show. Sony’s Beyond Sports engine and Hawk-Eye Innovations optical tracking are used to create the live animations during Funday Football, rebuilding in real time each throw, route, block, kick, and tackle — from which the audio mixers took most of their cues. This year, it also supplied SFX, such as the spiraling smoke trail behind a thrown football and the fire beneath running feet.

In addition, some of the actual “nat sound” of the game itself made its way into the animated show, in the replays of game plays, as did some of the game’s effects audio. This actual ambient audio was sent from the onsite broadcast mix to an Evertz video router in a media room adjacent to the Bristol audio-mix control room. Most of that was crowd sounds, pulled from the crowd microphones and parabolic reflectors deployed in the stadium, as well as the wireless mics on the field.

“I would kind of duck them down a little bit if I needed to while they were running the replay,” says Casey, who was also the A1 on the Toy Story and The Simpsons editions of the show. “We would get the clean nats from the truck [in Los Angeles], and I was also taking fake crowd nats from Finberg, who was in another control room downstairs from us, that I had coming on a fader, along with all of his cheers. But what we also needed to clarify was, should that include any kind of ref calls? Because, obviously, when you’re mixing a live game, you’re seeing the ref, and you’re hearing the ref. But, for us, it was a creative decision, and we decided to get clean nats from the game, no ref call, because, in the animated world, we weren’t seeing that. Instead, we had an animated whistle and an animated character that would throw up a flag.”

Media Magic

Whether it’s Mikey and Sully from Monsters, Inc. or Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck, Hollywood’s flagship animated productions are as famous for their technical complexity as for their memorable characters. The layback of audio to animation normally takes months of painstaking effort. To accomplish that on the fly for a live broadcast is its own kind of media magic.

“What’s really great about these productions is that it lets audio just do what we do,” says Severance. “They give us a lot of creative freedom, and Spike and all those guys trust us. That’s a huge thing in the industry: having that trust to say, ‘Okay, I can focus on calling the game and dealing with all the replays and not have to worry about audio.’ I think that’s a big relief on them. It puts a little pressure on us, but it also makes it a lot more exciting. We’re able to have all that creative freedom and not be locked into [a script].”

In fact, adds Finberg, the hardest part for him was trying not to have fun, to deviate from what is usually a highly structured production format and let the creative instincts that got people into audio in the first place run more freely.

“Most of the time when we’re mixing a show,” he explains, “we have the director in our ear, and everything is heavily scripted: if [the audio is] not the way it was scripted, then it’s on us, and it’s a problem. But, with this, it either goes well or goes poorly. If it goes poorly, it’s, like, ‘All right, just don’t do that again.’”