AI Is Deployed To Automate Audio Submix on MMA’s Pro Fighters League Matches

Custom software uses data from live video to track fighters, open/shut faders

Story Highlights

A couple of A1s have figured out how to make the Pro Fighters League’s cages a bit smarter for audio. Sean O’Gorman and Shawn Peacock, the A1 and comms manager/audio guarantee, respectively, on MMA league broadcasts on ESPN, ESPN+, ESPN Deportes, and related partners, are applying a version of AI to manage a complex effects mix.

They deploy their own custom computer-vision software to analyze live video to derive positional data that is used to manage the audio submix,

“One well-placed microphone is always better than three poorly positioned ones,” says O’Gorman, echoing a long-time music-production aphorism. “But, to really capture a PFL match, you need a lot more microphones, and they need to be managed over the course of five or six hours of a show. It’s a lot of work for a submixer.”

And even more for a single A1 who is also managing crowd sounds and roving announcers and other audio sources, even if O’Gorman and Peacock can tag-team each other over the course of a long fight.

Broadcasts of the PFL, the only MMA league with a regular season and a playoff structure, had never budgeted for a separate submixer, despite the rapid pace of the matches. That led O’Gorman and Peacock to develop the idea of taking data from a computer-vision system — which extracts information from images — and plugging it into bespoke software that would open and close the faders on the Calrec console as the fighters moved around the cage, keeping the sound effects focused on the action. In this case, their regular A2, Zach Templin, deployed a total of 19 microphones — three Sennheiser MKH-416 shotgun overheads, a combination of 10 416 and AKG P-170 perimeter mics, and six Sony ECM-55 under-mat mics — whose faders are activated by the software.

Managing Microphones

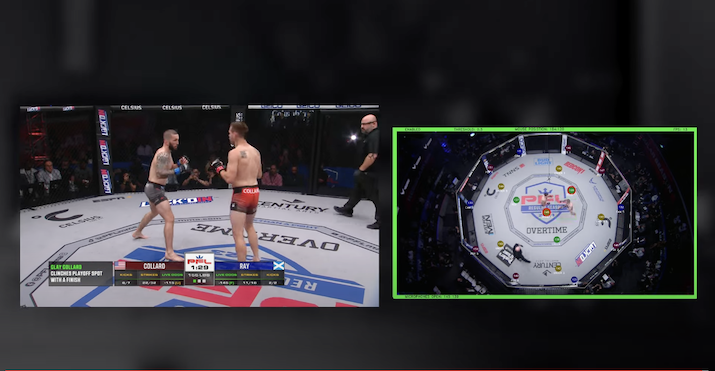

“We developed a computer-vision model that we trained to recognize fighters and only the fighters in a live single overhead-camera video feed,” O’Gorman explains, noting that the referee is excluded. “This vision model runs on a separate Mac Mini, where we also plot all the microphones inside the MMA cage into a 2D space. The model is able to detect the fighters, position them in the 2D space, and decide which microphones should be open to best cover the cage for that moment in time.”

The software also communicates with a Calrec Artemis console over IP using Calrec’s CSCP protocol, which allows two-way communication with the Artemis.

Mac Mini running custom software plots mic locations to open and close faders on Calrec Artemis console.

“We take a video feed from an overhead camera and feed that into a Mac Mini, which runs real-time computer-vision analysis and makes decisions on where the action is in the cage based on the fighter movements,” says O’Gorman. “Once the software and vision model decide what should be done to pick up the best audio in the cage, the software talks to the desk to move the faders where it wants.”

A Marriage of Two Technologies

O’Gorman and Peacock were already entrepreneurially active. This year, they launched Universal Remote.tv to create a service template that could pair a cost-effective remote-mixing platform with qualified A1s anywhere in the U.S. or elsewhere; it is intended to enable sports-broadcast audio to be mixed remotely, at a significantly reduced cost to the broadcaster and/or league, most of the saving coming from the absence of travel-related costs, such as airfares, hotels, and per diems. The automated-submixing concept deployed for PFL, which has not yet been named, is being developed under the Universal Remote.tv umbrella.

Both concepts, says Peacock, are based on reducing not only the personnel costs of sports broadcasts but also the workload on the audio-production staff. He and O’Gorman began developing the idea during a break in this year’s schedule and have applied it to six fights since the season restarted in April. It’ll be heard during Weeks 7, 8, and 9 in August and during the league’s championship matches in December.

O’Gorman notes that the concept is innovative but relies on existing technologies. In addition to the computer-vision data, the connection to the mix console also uses Calrec’s CSCP serial control protocol.

He says that he and Peacock asked themselves, “Why don’t we take these two technologies — the image-recognition video feeds and the serial connection — and write some software rules around that: here’s the microphone, here’s where it is in the cage; when these things happen, I want you to talk to the console and move these faders. It was the marriage of those two technologies. It’s a novel idea to have the two work together in the audio space.”

They believe there are applications for the concept for any sport that takes place in a well-defined space, including baseball and soccer. Productization could be tricky: it depends on the source, type, and amount of video-derived data available at a venue. But the actual components are fairly minimal: a Mac Mini and the custom software. And the concept arrives as broadcasters’ budgets continue to tighten, making it potentially attractive financially. All it might need is a catchy name.

“We’re working on that,” laughs O’Gorman.