Tech Focus: Immersive Audio — A Technology Awaiting Its Broadcast Infrastructure

The multilane highway to consumers is slowly being developed

Story Highlights

Immersive audio remains tantalizingly close yet frustratingly elusive. Substantial strides have been made with the concept for certain applications, such as music production, driven largely by Dolby and its Atmos format, which has been heavily marketed to record producers, engineers, and labels. Live sound has also turned an immersive corner: systems from leading brands, such as L-Acoustics and d&b audiotechnik, offer venue-encompassing sonic experiences. Most notably, the debut of the Sphere, a new performance venue on the Las Vegas Strip that opened in September with a residency by U2, takes immersiveness to an extraordinary level: its sound system comprises a mind-boggling total of 167,000 individually amplified speaker drivers.

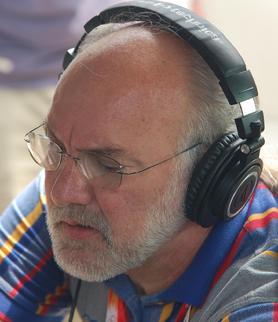

Immersive-audio advocate Dennis Baxter: “Simply put, it’s hard to get immersive sound to the home [via streaming].”

The Formats Are There

Broadcast was one of the first targets for the immersive sector, just after cinema. Both environments have a reasonable expectation of audience cooperation when it comes to staying in a predictable seat location and head orientation — critical elements for a full experience of immersive sound. And broadcast has plenty of format options: besides AC-4, the Dolby Atmos broadcast iteration and the primary immersive format for the forthcoming ATSC 3.0 protocol, and MPEG-H, the Fraunhofer Institute’s entry that has made some headway in European and Korean broadcast sectors, there’s also Auro-3D and Sennheiser’s AMBEO.

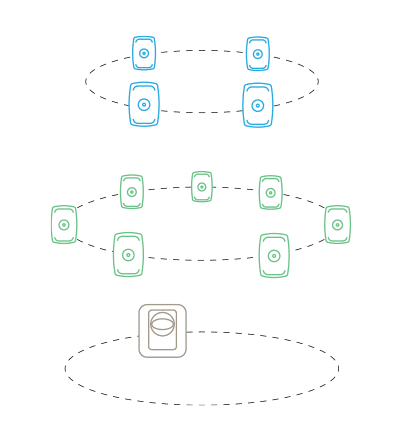

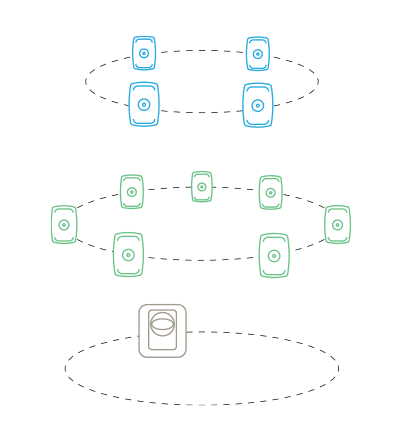

Here’s a look at the main formats available. (Graphic illustrations are courtesy of Genelec.)

Dolby Atmos (Atmos Fig. 1)

Launched in 2012, Dolby Atmos is a widely supported object-based system with up to 128 individual tracks and 64 speaker feeds.

- Two-layered system with both surrounds and height channels

- Typically, up to 7.1.4 for home reproduction, but larger speaker layouts are possible

- Up to 64 discrete speaker feeds for cinema reproduction

Auro-3D

Introduced in 2006, Auro-3D is a channel-based three-layer system that comes in a variety of formats.

- Three-layer system with surround, height, and VoG channels

- Typical formats from 7.1.2 to 7.1.6.

- Object-based AuroMax extension for additional channels

360 Reality Audio

Introduced in 2019 by Sony, 360 Reality Audio uses object-based spatial technology to deliver a full 360-degree audio experience.

- Three-layer system with channels above, below, and surrounding the listener

- Can be experienced on certified loudspeakers and also on headphones, via compatible music-streaming services

- Does not use a dedicated LFE channel, but subwoofer(s) can be used for bass management

MPEG-H Audio

Developed by MPEG for broadcast and streaming applications, the MPEG-H Audio system brings immersive sound and advanced personalization and accessibility features.

- Scalable architecture allows flexibility in number of channels

- Audio objects enable dialog enhancement and personalization

- Empowers creation and delivery of a high-quality immersive music experience

22.2

Developed by Japanese broadcaster NHK, the three-layer channel-based 22.2 system forms the surround-sound component of NHK’s Ultra HD television system.

- Three-layer system for broadcast and home use

- Fixed number, fixed channel positions for production

- Full or condensed home reproduction systems

DTS:X

DTS:X was launched in 2015. Like Dolby Atmos, it is an object-based system but without prescribed speaker configurations.

- Two-layer system with surround and height channels

- Audio rendering based on number and position of speakers available

- Supports up to 32 speaker locations and 7.2.4 channels

ITU-R and Pure Research

ITU-R is researching the requirements for realistic 3D sound for UHDTV. Pure research is focused on in-room and binaural sound with and without movement.

- At least three vertical layers and one or more subs

- Typically between 11 and 80 main channels

- ITU-R is collaborating with NHK (Japan), SMPTE (U.S.), and EBU (Europe).

An Inflection Point

Immersive broadcast seemed to have its own inflection moment when, at the 2012 London Olympics, Japanese public broadcaster NHK unveiled its Super Hi-Vision project, offering 22.2 channels to match the production’s 8K picture to create an immersive audio experience.

Despite the promise of immersive audio for broadcast, however, the infrastructure required to make it a mass-market consumer product has moved forward only slowly: the broadcast distribution chain from networks to individual stations is not yet widely ready to handle the new immersive formats, and, in any event, the base of NextGenTV-capable home sets is still quite small. And broadcasters are still working on the processes necessary to comply with the FCC mandate to ensure that 3.0 content will be compatible with the 1.0 world most people live in.

“Simply put, it’s hard to get immersive sound to the home [via streaming],” says Dennis Baxter, an educator, a consultant whose portfolio includes sound design for nine Olympic Games, and an advocate of 360-degree audio. Sound bars are the key to uptake of the format, he says, and on-air mixes have to reflect that. Furthermore, he notes, television sets are evolving away from useful built-in speakers, which means that consumers have to proactively add ancillary equipment — soundbars, headphone-based monitoring, full-blown 5/7.1.4 speaker arrays — to access and fully enjoy immersive audio.

In the meantime, broadcast-sports A1s must continue to develop immersive mix techniques that go beyond simply putting crowd sounds in overheads and surround channels. Instead, effects microphones, such as those focused on the nets in basketball, need to have predictable and prominent places in broadcast mixes.

However, Baxter adds, “the real problem is infrastructure. There’s a lot of work ahead.”

In a sense, it’s the surround conundrum redux: most primetime broadcast content now is produced in 5.1 surround sound even though most consumer televisions in use and for sale are overwhelmingly stereo (at best).

Still on the Agenda

Immersive sound remains a goal for broadcast audio, as demonstrated by new products and processes, such as Audio-Technica’s relatively new 8-channel BP3600 surround microphone and Sennheiser’s new AMBEO 2-channel spatial-audio system for live-broadcast applications.

And network sports divisions and sports organizations, leagues, and teams are making individual moves toward building infrastructure and best-practice regimens around immersive. For example, NBC Sports has deployed Atmos for Notre Dame home games for years, and the NHRA has use the technology for drag races in the recent past. Future Olympics broadcasts are going to be in Atmos, as they have been in the U.S. since the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Games. And Atmos continues to be used in the UK by Sky Sports and BT Sport for Premier League and Championship League soccer on 4K channels.

Immersive audio for broadcast sports is clearly headed for the day it becomes the norm instead of a novelty. But much like the automobile more than a century ago, it’s just waiting for better roads to be built for it.